For my midterm project, I want to make a nail salon game in p5.js. The idea is that customers come in, and the player has to design nails that match how they feel. I want it to be more than just picking random colors, so their mood is what makes the game more creative. I also want to include a mood-guessing game at the beginning. The customer will say a short line, and the player will guess their mood before starting the nail design. Then the player designs the nails based on that mood, and the game gives feedback at the end.

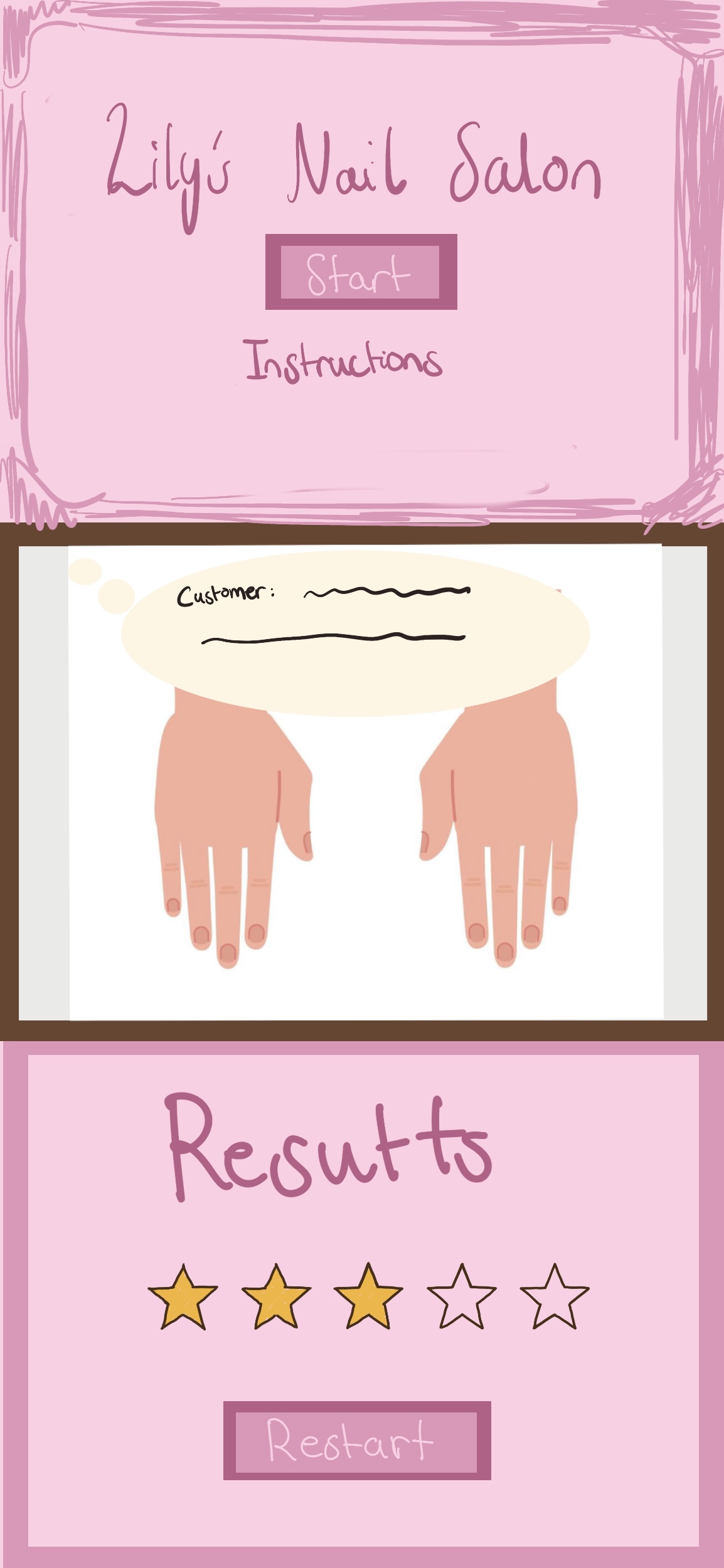

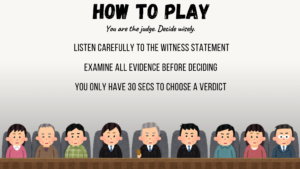

I want the design of the project to look cute, simple, and easy to understand, like a cozy nail studio. I plan to use soft colors and clear buttons so the user can move through the experience without getting confused. The project will start with an instructions screen, then move to the main nail salon screen where the customer says their line and the player guesses their mood, then the player designs the nails, and finally sees a result screen with feedback and a restart option.

For the visuals, I will use shapes for the nails, buttons, and decorations, and images for things like the background or customer. I also plan to include sound and text for the customer’s reaction/line so the project feels more interactive. This is a sketch of what I’m planning for my game.

I think the most challenging part will be organizing the project and the code, and making sure everything appears at the right time. Since the project has multiple stages, I need to keep the flow clear and make sure the user knows what to do next. Another challenge is the nail design interaction itself. I still need to decide the simplest and best way for the player to apply colors and decorations. I want it to be easy to use, but still feel fun and creative. I also still have not figured out how to decide whether the final design matches the customer’s mood at the end or not.

To reduce that risk, I will first make a simple version of the project with only the screen flow and text/colors. This will help me test if the structure works before I spend time on the final visuals. I will also make a reusable button class early so I can use it for mood choices, color choices, and the restart button. After that, I will test the nail design interaction with basic shapes first, like clicking a button to change the nail color, and I may also try a brush-like stroke animation.