My midterm project, The Polyglot Galaxy, is an interactive generative text artwork that visualizes multilingual greetings as floating stars in a galaxy environment. The project expands on my Week 5 text generator into a more immersive interactive media system that integrates text, sound, animation, state-based interaction, and computer vision.

As each time the user clicks on the canvas, a greeting phrase from a different language is stamped onto the screen. Over time, these phrases accumulate and form a constellation-like galaxy. Within the frame, it will display 4 different voices. The visual aesthetic is inspired by space, glow, and floating motion, which represents languages as stars in a shared universe.

For Week 6, I introduced webcam interaction as a form of real-time input. Instead of functioning only as a background element, the camera actively influences the visual behavior of the system. The brightness detected from the live webcam feed controls the twinkling speed and intensity of the text objects. This transforms the artwork from a static generative system into an embodied interactive experience where the audience’s movement directly affects the visuals.

function updateCamBrightness() {

cam.loadPixels();

let sum = 0;

for (let i = 0; i < cam.pixels.length; i += 40) {

let r = cam.pixels[i];

let g = cam.pixels[i + 1];

let b = cam.pixels[i + 2];

sum += (r + g + b) / 3;

}

camBrightness = sum / (cam.pixels.length / 40);

}

I am particularly proud of successfully integrating computer vision into a generative art system in a simple yet meaningful way. Rather than just implementing complex face detection (which would be rather computationally heavy and technically advanced), I chose brightness-based interaction. This decision balances technical feasibility, performance efficiency, and conceptual clarity.

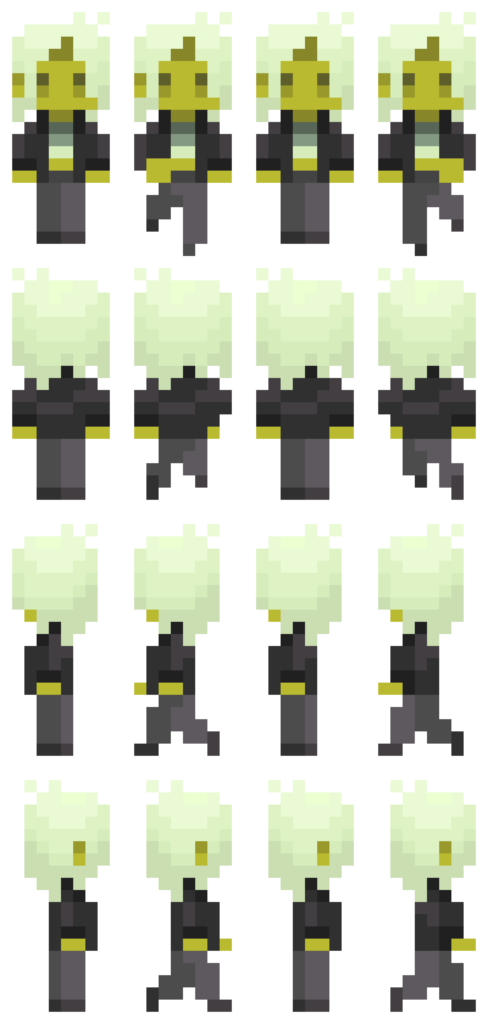

Moreover, I am also proud of the object-oriented structure of my code. The GreetingText class encapsulates the floating animation, glow effects, blinking, and camera-reactive twinkling within a reusable system. This makes the project scalable and organized as more text objects are generated over time.

One major challenge I encountered was browser permission and issues related to the webcam. In some environments, the camera feed just doesn’t function unless the sketch runs in a secure (HTTPS) context or after the user grants camera permission. I addressed this by using the webcam primarily as a data input rather than relying on it as a visible visual component.

For improvements I would like to imagine as we know after the midterms we would be focusing on more hardware related stuff and therefore I would like to incorporate the functions of a camera where if you swipe left it would display a phrase in a language and if you swipe right it would display another language in another phrase and if you swipe up does another phrase in another language.

References

-Course Lecture Slides: Week 6 – Computer Vision & DOM (Introduction to Interactive Media)

-Daniel Shiffman, p5.js Video and Pixels Tutorials

-p5.js Documentation: createCapture(VIDEO) and pixel processing

-Creative Coding approaches to camera-based interaction in interactive media