(up to two players! WASD for top side and IJKL/arrow keys for bottom side)

I thought about how I wanted to build upon what I had last week and I arrived at the idea of using something to interact with the bouncing ball mechanic. At first, I thought about making an air hockey game where you could drag the paddle but I didn’t know how to create an opponent that could respond to what you do. And it couldn’t be multiplayer since there’s only one mouse, which led me to using keyboard keys to control the paddles.

I began to build two separate objects that can be controlled by wasd and arrow keys respectively– a lot like the old web games I would secretly play in my computer science class with my classmates back in elementary school.

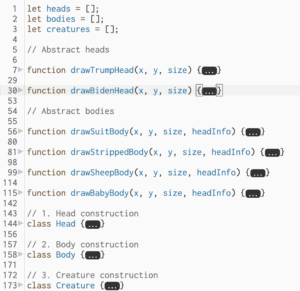

Using Classes and this.

Last week when I presented my project to professor Aya, she suggested that I learn how to use class so I could make it easier on myself to organize my code and objects. So this week I delved into classes and have a pretty good grasp on it now. Here are two classes I made– the ball and the top paddle.

class ball { //class creates a re usable template: let ball1 = new ball(x,y,r)

constructor(xPos, yPos, radius){ //creates the initial state

//this referes to the object currently being created

this.xPos = xPos;

this.yPos = yPos;

this.radius = radius;

this.ballXspeed = ballXspeed;

this.ballYspeed = ballYspeed;

this.ballMoving = false; //boolean to help reset ball

}

move() { //this is a method, a function that belongs to just one object

if (!this.ballMoving) return; //if ball is still then do nothing

this.xPos += constrain(ball1.ballXspeed, -maxSpeed, maxSpeed)

this.yPos += constrain(ball1.ballYspeed, -maxSpeed, maxSpeed)

//BOUNCE: CHECKS LEFT AND RIGHT EDGE

if (this.xPos > width - this.radius || this.xPos < 0 + this.radius) {

this.ballXspeed *= -1;

}

}

reset(){

this.xPos = width/2;

this.yPos = height/2;

this.ballMoving = false;

//setTimeout(function, delay) delay is in milliseconds

setTimeout(() => { //the arrow =>

this.ballXspeed = random([-ballXspeed, ballXspeed]);

this.ballYspeed = random([-ballYspeed, ballYspeed]);

this.ballMoving = true;

}, 2000);

}

scoreDetection(){

//CHECKS TOP AND BOTTOM EDGES

if (this.yPos > height - this.radius) {

adjustScore(1,0); //top side scores 1

this.reset();

}

if (this.yPos < 0 + this.radius) {

adjustScore(0,1); //bottom side scores 1

this.reset();

}

}//closes score detection

display(){

ellipse(this.xPos, this.yPos, this.radius *2);

}

} //ends class ball

class topPaddle {

constructor (xPos, yPos, paddleWidth, paddleHeight, xSpeed, ySpeed){

this.xPos = xPos;

this.yPos = yPos;

this.baseY = yPos; //initial yPos

this.paddleWidth = paddleWidth;

this.paddleHeight = paddleHeight;

this.xSpeed = xSpeed;

this.ySpeed = ySpeed;

}

display(){

fill(255)

rect(this.xPos,this.yPos,this.paddleWidth,this.paddleHeight);

}

move(){

/* Keycodes

W = 87

A = 65

S = 83

D = 68

*/

if (keyIsDown(87)){ //TOP

this.yPos += this.ySpeed * -1; //negative because 0 counts down

}

if (keyIsDown(65)){ //LEFT

this.xPos += this.xSpeed * -1;

}

if (keyIsDown(83)){ //BOTTOM

this.yPos += this.ySpeed ;

}

if (keyIsDown(68)){

this.xPos += this.xSpeed;

}

//RESTRICTIONS

this.xPos = constrain(this.xPos, xBoundary, width-xBoundary)

this.yPos = constrain(this.yPos, this.baseY-yBoundary, this.baseY+yBoundary)

} //closes move()

}

I really enjoyed using methods to help organize my code and operate on an object-oriented basis.

Not too far into writing the classes for the paddles, I realized I was recreating the game pong. This is literally how pong was made– someone wanted to test bouncy ball physics and moving paddle collision and made pong.

Implementing Arrays

I already experimented with arrays last week when dealing with for() loops so this week I wanted to use them in a different way: to track scores for each side. I made two arrays– one called topCounter and one called bottomCounter. If the top side won round 1, they would have 1 added to their array and have it console.log’d into the console.

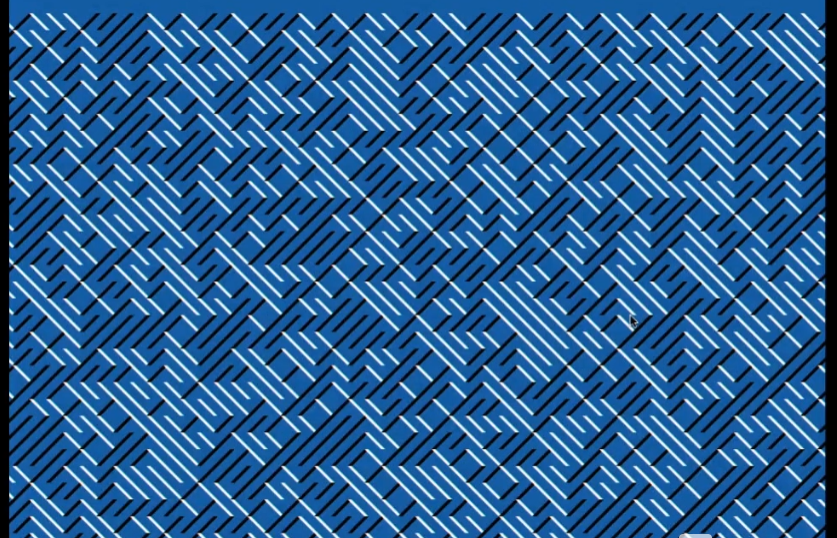

Designing with Variables

Since we learned push() and pop() in class last week, I’ve been wanting to use these techniques to make more organized stroke() and strokeWeight() functions.

Beyond that, I used a lot of variables to help with the numbers so changing the variable number in the top of the code would change all of the related values throughout the code conveniently and often symmetrically. For instance, I would get the midpoints between the two ends of the lines to have the score number displayed there.

//LEFT CENTER LINE

line(

0,height/2,

0+sideLineMargin,height/2

)

//CENTER LINE

line(

(width/2)-centerLineMargin,height/2,

(width/2)+centerLineMargin,height/2

)

//lots of code inbetween

// TOP SIDE SCORE

text(topScore,

((width/2)-centerLineMargin + 0+sideLineMargin)/2,

height/2

)

I also found the rectMode() and textAllign() functions to be incredibly helpful.

Adjust Gameplay Parameters

Initially, the back and forth between the two players felt very predictable and un-engaging. It was slow and ran at a consistent speed, which also meant there was only so many things you could do to change the trajectory of the bounce.

So I did two things, I made the paddles have way more vertical movement than it did initially, and I added a speed multiplier that really shaked the game at its core.

Every time a player would collide their paddle with the ball now, the ball would speed up by 4%, which is seemingly small, but builds up very quickly to overwhelm players.

//BALL ATTRIBUTE

let ballXspeed = 6;

let ballYspeed = 5;

let speedUpFactor = 1.04; //105% each time it collides with paddle

let maxSpeed = 14; //limits the speed of the ball

//lots of code inbetween

if (ballCollidePaddle(ball1,topPaddle1,"Bottom")){

ball1.ballYspeed *= -1;

ball1.ballXspeed *= speedUpFactor;

ball1.ballYspeed *= speedUpFactor;

}

However, it would get to a point where p5js wouldn’t really render it at a high enough fps for it to be fair to the players, so I added a max speed cap of 14-ish into the move() method for the ball to make sure it would be fast but not too the point of absurdity.

Difficulties Endured

Thankfully p5js didn’t crash half a dozen times during the development like it did last week, but I had some technical struggles.

When I built the second paddle object in the bottom, I completely forgot to constrain the y-value of the paddle which created quite a humorous moment when my girlfriend wanted to test the paddle movement with me.

The math behind colliding a circle with a rectangle was pretty confusing to figure out, but I also didn’t want to use circles as paddles so I tried a lot of methods until I made it work by checking the x-edges overlapping.

let xOverlap =

(ball.xPos + ball.radius > paddle.xPos - paddle.paddleWidth/2) &&

(ball.xPos - ball.radius < paddle.xPos + paddle.paddleWidth/2);

if (!xOverlap) return false; //checks if ball collided with paddle early

When I tried to embed it onto wordpress, the arrow keys kept trying to scroll the embed for me so I had to add another set of controls on IJKL.

Gameplay Strategy & Technique

In testing my friends and I found a few strategies and techniques that help with winning rounds. One of the strategies is to back up as the ball approaches max speed; this really helps by giving you more time to react and save the ball.

Another technique we accidentally found out was double-tapping the ball to have it gain the speed multiplier several times on the same receive.

My friends and I had jolly fun playing against each other even if they thought the game was incredibly difficult.

Conclusion

I had a lot of fun making this project and learning how to use more tools in JavaScript. Making classes felt like an essential part of JS coding that I finally understood today. I can really feel my progress growing every week with every assignment.

I really hope I can repurpose the work I did in this project sometime in the future or even just play it with my friends whenever I open my p5js account.