Concept

For my midterm project, I came up this dining hall idea at the last minute. I had originally been inspired by music interactivity in p5.js and considered continuing with my earlier idea of a meditation game. But while eating lunch, I came up with a new idea that felt both playful and relevant to my experience here at NYUAD. So, I mostly working on replanning my idea and preparing assets this week.

As a visiting student from the New York campus, I was used to the dining hall’s pre-made meals. But At NYUAD, the on-demand menus were at first a little overwhelming. Without pictures, I often had no idea what I had ordered (especially with Arabic dishes I wasn’t familiar with) and I even found myself pulling out a calculator to check how much I had left in my meal plan and how much I orderd. Counters like All Day Breakfast felt especially confusing.

So my concept is to digitalize the experience of eating at NYUAD’s D2 All Day Breakfast counter. The project will let users visualize the ordering process, making it more interactive and hopefully reducing the friction that comes with navigating the real-life menu.

User Interaction

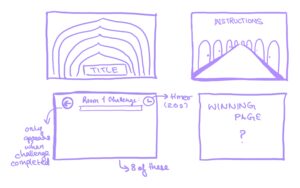

Planned Scenes (prototype):

1.Entering the A LA BRASA counter and tapping into the menu

2.Picking up the clamp to get food from the grill to the plate

3.Scanning food on the plate at the cashier’s scanner

4.Paying with coins in the cashier tray (display receipt?)

5.Eating!!

6.Burping to finish the meal

Assets:

Audio:

Dining hall ambient background

Cashier scanner beep

Cash register “kaching”

Burp sound

Yumyum sound

Pixelated images:

A LA BRASA counter background

All Day Breakfast menu

Grill plate

Clamp

Plate

Cashier scanner

Cashier with coins tray

Coins (D5, D3, D2, D1, D0.5, D0.25)

Fork

Pixel art food items:

Avocado fried egg toast

Avocado toast

French toast

Fried egg

Scrambled egg

Plain omelet

Cheese omelet

Mixed vegetable omelet

Tofu omelet

Hash brown

Chicken sausage

Beef bacon

Turkey bacon

Classic pancake

Coconut banana pancake

small bowl salad

The Most Frightening Part & How I’m Managing It

The biggest challenge I anticipate is gathering and aligning all these assets into a coherent game within the midterm timeframe. Real-life food images can be messy and hard to unify visually. To reduce this risk, I’ve decided to make everything in pixel art style. Not only does this match the “breakfast game” aesthetic, but it also makes it much easier to align items consistently.

Since Professor Mang mentioned we can use AI to help generate assets, I’ve been experimenting with transforming photos of my own plates and my friends’ meals into pixelated versions. This approach makes asset creation more manageable and ensures I’ll be able to integrate everything smoothly into the game.