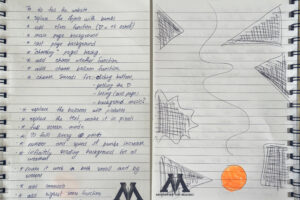

Overall Concept:

This is Pong². It’s called Pong² because this isn’t just a spiritual successor to the first ever video game, it’s a dimension beyond. If regular pong only moved you in one axis, it only has one dimension; this game lets you move left to right AND back and forth– creating a very amusing experience with much more depth than the original.

Pong² features two modes. Let’s start with Versus. Versus is a continuation of what I worked on all the way back in Week 3. In Versus, you and another player play a 1 v 1 duel of up to 9 rounds, best of 5. It’s the same win conditions as classic pong but with a lot more strategic depth. Moving your paddle in the opposite direction towards the ball will “smash” or “spike” it into your opponent’s side while moving in the same direction as you receive the ball will help you “control” or “trap” it.

Pong²’s second mode is its best: co-op. In Co-Op mode, you and another player work together to guard the bottom goal against multiple balls that speed up with every return. You have 3 lives and each ball that slips past you takes a life from your shared life total. You have to coordinate with your teammate to make sure you keep a watch on every ball and not just respond as fast as you can to each one, because that’s only going to take you so far (my bet is on 50 seconds).

Feedback: Color Scheme Consistency

On our Monday checkup, Professor Ang told me to have consistent colors for highlighting the gameplay instructions; when I use different colors to highlight I risk player confusion. I also proceeded to keep the game mode colors consistent with the menu instead of having the menu remain exclusively white and purple.

CO-OP Mode Design

I originally planned to make a player vs AI mode but realized that I really didn’t know how to make it respond similarly to how a real player would move the paddle. I had received feedback from Professor Ang to make the concept more interesting than just the usual 1v1 pong, and that’s when it hit me: what if I made 2 Player survival pong?

I had a lot of fun designing the co-op mode on paper, but I made my code a huge mess by duplicating my versus game mode javascript file instead of working from scratch. I THOUGHT that would make the process faster since I would be working with my previous framework but I ended up having to modify so many things it ended up convoluting it.

I originally had the game start with just one ball and you wouldn’t get the second ball until the 15th hit on the top side; however,I realized I wanted players to naturally have the idea to coordinate with each other. For instance, player one might tell his teammate “I’ll take the red ball you take the blue one” to strategize. So what I decided was to make the 15th hit spawn the third ball and the 2nd top bounce spawn the second ball which presents the challenge to players at a good pace.

I was very proud of this for loop I built to manage the many colorful balls that you had to defend against. Between this week and last week, I also had to add a canHitPaddle() method and timer to make sure you wouldn’t accidentally double hit the same ball as you tried to move in the same direction as it.

for (let b of coopBalls){ //runs thru all the balls stored in the array

b.display();

b.move();

b.scoreDetection();

if (coopBallCollidePaddle(b, player1paddle1, "Top")&& b.canHitPaddle()) {

paddleBounceNeutralSFX.play();

b.lastHitTime = millis() //records hit time using canHitPaddle()

b.ballYspeed *= -1;

b.yPos = player1paddle1.yPos - player1paddle1.paddleHeight / 2 - b.radius - 5;

if (keyIsDown(83)) { // 'S'key

paddleBounceControlSFX.play();

b.ballYspeed *= COOPbackControlFactor;

} else {

paddleBounceNeutralSFX.play();

}

}

if (coopBallCollidePaddle(b, player2paddle1, "Top")&& b.canHitPaddle()) {

paddleBounceNeutralSFX.play();

b.lastHitTime = millis()//records hit time using canHitPaddle()

b.ballYspeed *= -1;

b.yPos = player2paddle1.yPos - player2paddle1.paddleHeight / 2 - b.radius - 5; //the 5 helps make a microadjustment to prevent funky collisions

if (keyIsDown(DOWN_ARROW) || keyIsDown(75)) { // '↓' or 'K' key

paddleBounceControlSFX.play();

b.ballYspeed *= COOPbackControlFactor;

} else {

paddleBounceNeutralSFX.play();

}

}

}//closes for b loop

I think the co-op mode overall turned out very well. It was surprisingly challenging but also a good amount of fun for the friends that I asked to test it.

VERSUS Mode Improvements

I had the idea to add direction input with forward and backward velocity. Basically say you’re on the bottom side, if you receive the ball with “down arrow” then you slow it down because you pressed the same key the ball was headed, but if you received it with the “Up arrow” key you would add momentum to it.

I had so much fun implementing this layer of complexity to the game. A main criticism I received at first was that the extra dimension of movement for the paddles didn’t offer a significant difference to the usual pong gameplay loop.

This was my response to that– adding a much needed strategic depth to the game. You weren’t just competing on who was better at defense now, you were seeing who had the better attack strategy.

In fact I originally didn’t plan to add this forward and backward velocity effect to the co-op mode but I loved how it felt so much that I knew I had to add it in some way. This posed a balancing challenge as well; if we were to keep the backControlFactor from the versus mode then it would prove far too easy.

Sound Design

I originally wanted to implement the sounds into my versus mode but then I realized building the infrastructure for all the menus first would make my life a lot easier. So sound design ended up as the last thing on the to-do list.

I usually got sound effects from silly button websites when I needed to edit videos so I never knew where to get actual licensed SFX for indie games. I eventually found one called pixabay that had a good list of sound effects.

Most of the menu button SFX and game over SFX were pretty straightforward, but I really wanted the SFX for the gameplay loop itself to sound very satisfying. My favorite ones were definitely the ball control SFX and the countdown SFX. For the ball control SFX, I was inspired by the sound design in the Japanese anime Blue Lock– which has some incredible sound effects like the bass-y effect when one of the characters controls the ball midair. I found this super nice sounding bass sound and that’s how the idea of using acoustic instrument sounds stuck. The other two ended up being a snare and a kickdrum sound.

Difficulties Endured

The Great Screen Changing Mystery

There was this incredibly confusing bug that I never truly figured out but the gist was that it would randomly switch screens specifically to the versus game mode SOMETIMES when I clicked into Co-Op.

I dug and I dug through the code endlessly until I saw that I left one of the screen-related if-statements to give an else-statement that defaulted the screen to versus. This was here for earlier tests but this seriously still doesn’t make any sense to me. There was never a call to the function that would switch to versus and there was nothing that would leave the screen state invalid for any of the available screens to take over.

This was a frustrating gap in my knowledge that I never fully understood, but I did fix it.

Hit “K” to Let the Ball Through (and look stupid)

For some reason, the bottom paddle kept letting the ball straight through whenever I blocked it while holding “K” or the down arrow. This took hours of looking for the problem, going “I’ll deal with that later” and then running into it again and wondering what the heck is causing this?

It was very specifically the bottom paddle and it HAD to be related to backward movement input detection. Then I realized that it was ONLY the bottom paddle because I had set the ball speed to minSpeed, which is always positive. So all I had to do was to convert it to a negative value equivalent to minSpeed.

if (keyIsDown(UP_ARROW) || keyIsDown(73)) { // '↑' or 'I' key

paddleBounceSmashSFX.play();

ballforVS.ballYspeed *= fwdVelocityFactor;

} else if (keyIsDown(DOWN_ARROW) || keyIsDown(75)) { // '↓' or 'K' key

paddleBounceControlSFX.play();

ballforVS.ballXspeed = minSpeed;

ballforVS.ballYspeed = minSpeed;

} else {

paddleBounceNeutralSFX.play();

}

Cursor Changing

When I was developing the buttons, I realized that they didn’t really feel clickable. So I wanted to add some code to change the cursor to the hand whenever it hovered over a button. This proved surprisingly complicated for what is seemingly an easy task. The most efficient way I found was to append all the buttons to an array for each menu and have it checked in a for loop everytime– then closing off with a simple if-statement.

function updateCursorFor(buttonArray) {

let hovering = false;

for (let btn of buttonArray) {

if (btn.isHovered(mouseX, mouseY)){

hovering = true;

}

}

if (hovering) {

cursor(HAND);

} else {

cursor(ARROW);

}

}

Conclusion & Areas for Improvement

As for areas of improvement, I would probably make the ball-paddle collision logic even more stable and consistent. It usually behaves predictably and as intended but it sometimes shows the way I coded it has a lot of flaws with colliding on non-intended surfaces.

However, despite all this, I am really proud of my project– both from the UI design standpoint and the replayability of the gameplay loop. Once my other friends are done with their midterms I’m gonna have a much better opportunity to see flaws in the design.