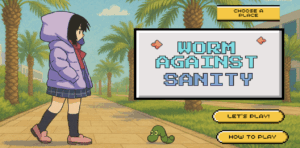

Concept

Food has always been something deeply emotional forme a way to heal, connect, and recharge after long or lonely days. Whether it’s sharing a meal with friends and family or eating quietly in solitude, food always finds a way to lift the spirit. For me, food is more than just fuel; it’s comfort, joy, and sometimes even memory itself. Every dish I eat reminds me of a moment, a feeling, or a person.

But, of course, there’s another side to that relationship those unforgettable moments when something unexpected shows up in your food: a hair, a fly, a worm, even a tiny stone. It’s disgusting, sometimes shocking, and yet over time it becomes something you laugh about. The idea for this project actually struck me when I once found a fly in my food. In that split second, my emotions bounced between anger, disgust, and disbelief and then, later, laughter. I realized how something so small could completely shift my mood and turn an ordinary meal into a story I’d never forget.

It also reminded me of moments with my grandmother. She used to cook for the whole family, and occasionally, there would be a stray hair in the food. Instead of getting angry, I’d turn it into a lighthearted joke so everyone could laugh. Those moments became cherished not because the food was perfect, but because the imperfections made it real, made it ours. They were messy, human, and full of love.

Through my project, I wanted to recreate those shifting emotions from disgust and frustration to humor and warmth. I tried to capture the entire emotional cycle we experience in those moments: the anger when something feels ruined, the creepiness of noticing something “off,” and the humor that comes when you finally laugh it off.

-

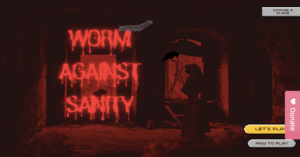

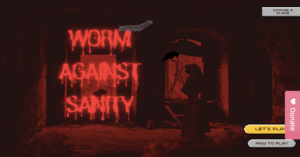

Anger is portrayed through intense, chaotic visuals like the “deadly” appearance of the dining hall, the harsh red tones.

-

Creepiness comes through the eerie atmosphere the bloody dining hall textures, dim lighting, and strange, almost horror-like visual style that makes you feel uneasy, the same way you feel when you find something in your food that shouldn’t be there.

-

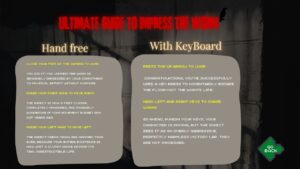

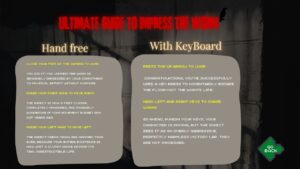

Humor ties it all together. I added funny instructions like “Ultimate Guide to impress Worm” that turns disgust into comedy. It’s a playful reminder that these moments, while annoying, are also absurd and relatable something we can laugh about later.

To make it more personal, I brought in imagery from NYUAD specifically D2 and the Library, two of my favorite places on campus. They hold countless memories of food, laughter, and friendship, so I wanted to reimagine them in my project. I took photos and used ChatGPT to generate artistic, surreal versions of these spaces blending reality and imagination. The result is an environment that feels both familiar and eerie, mirroring that strange feeling of discovering something unexpected in what you love.

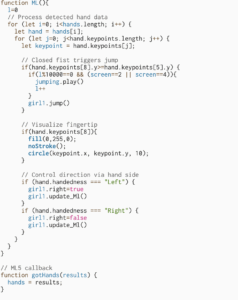

Lastly, I chose to use hand gestures as one of the interaction method because I wanted the experience to feel physical and expressive, not just mechanical. In real life, our hands are what connect us to food. We cook with them, eat with them, react with them. So, using gestures like moving the left hand to go left, right hand to go right, and closing the fist to jump feels symbolically and emotionally right. It mirrors how our hands instinctively respond when we’re disgusted or startled. We pull back, push away, or clench up.

While it might not be the most conventional control scheme, that’s precisely what makes this project unique and artistic rather than a simple computer game. The goal wasn’t to make a polished arcade game, but to create a more embodied experience one that makes the player aware of their own physical reactions.

How to Play:

At its core, the project is an interactive game centered around a simple but expressive idea: defeat the worms that are being generated from right of the screen before they reach the end of the screen on left.

Players can interact with the game in two different ways:

Keyboard controls — using the arrow keys to move and jump: → to go right, ← to go left, and ↑ to jump.

Hand gesture controls — raise your left hand to go left and raise your right hand to go right. By raise I mean make your hand visible to the camera and when u don’t want to go say left make you left hand unvisible to the sight of the camera. If you make a fist or close your finger the girl will jump.

The basic rule is simple: jump over the worms to eliminate them before they cross the screen. Players have three lives, and if they manage to survive until time >= 900 (meaning the draw function has run 900 times) with at least one life left, they win.

At first, it might feel unintuitive, but as you play, it becomes surprisingly fun and natural like you’re physically fighting off those unwanted “guests” in your meal.

Parts I’m Proud Of

The part I’m most proud of is integrating Machine Learning into a project that’s not only technical but emotional and personal. As a Computer Science major, I’m always drawn to exploring how technology can express feeling and creativity. Implementing gesture control allowed me to bridge art and code to make something that doesn’t just work, but feels alive.

I’m also proud of how I personalized the experience. By using NYUAD-specific places like D2 and the Library, I rooted the project in a world I know and love. It gives the game a familiar atmosphere one that other NYUAD students can relate to while still transforming it into something strange and artistic.

Areas for Improvement

While I’m proud of how the game turned out, there are several areas I’d like to refine. The hand gesture control, though innovative, can feel slightly clunky at first. I’d like to make it more responsive and intuitive perhaps by training the ML model with more data or maybe using ML to detect body that can say if a person is turning left or right and the character themself move left or right.

I’d also love to expand the visual storytelling. Right now, the “bloody” D2 gives the right kind of creepiness, but I imagine adding more levels or moods maybe transitioning from a calm dining scene to a chaotic food fight as the difficulty increases.

Problems that you ran into

While building the project, I faced a few interesting technical challenges that pushed me to think creatively about how motion and input are detected and processed.

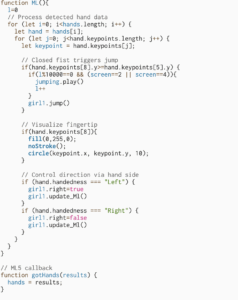

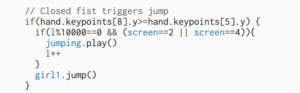

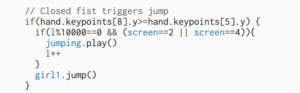

1. Detecting when the hand is closed (fist gesture):

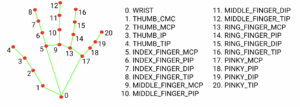

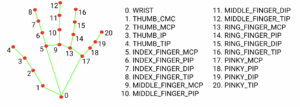

My first major challenge was figuring out how to detect when the user’s hand is closed. I wanted the “fist” gesture to trigger a jump action, but at first, I wasn’t sure which hand landmarks to compare. Eventually, I decided to track the index fingertip (keypoint 8) and the base of the index finger (keypoint 5).

The idea was simple: if the y-coordinate of the fingertip (hand.keypoints[8].y) becomes greater than that of the finger base (hand.keypoints[5].y), it means the fingertip is lower in the camera frame in other words, the finger is curled in, forming a fist.

I used console.log(hand.keypoints[8].y, hand.keypoints[5].y) to visualize the values and experimented by opening and closing my hand repeatedly to see when the condition triggered. This trial-and-error approach helped me fine-tune the threshold for reliable gesture recognition. It was satisfying to see the jump action respond accurately once the logic clicked.

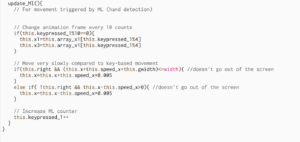

2. Managing repeated function calls with hand gestures:

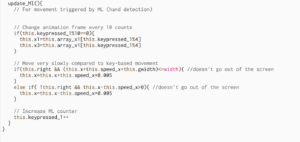

The second issue was with repeated trigger events when using gesture control. Unlike pressing a key which calls the action just once per pressraising a hand is a continuous motion, so the detection function kept firing dozens of times per second.

For example, calling girl1.jump() or movement functions using hand gestures caused the action to repeat uncontrollably fast. To solve this, I implemented a counter-based system and used a modulus condition to limit how often the action executes. Essentially, if the function was being called too rapidly, I only allowed it to execute once every ten calls.

Similarly, I adjusted the character’s movement speed when controlled by gestures. Instead of moving by this.speed_x each frame (which made her move unrealistically fast), I scaled it down to this.speed_x * 0.005 inside the update_Ml() function. This made her movement smooth and proportional to the natural pace of a hand gesture, giving the game a more balanced and controlled feeling.

This also applied to animation strip changes by updating them every tenth frame, the animation stayed visually consistent without flickering or overloading.

My Sketch :

view only screen link: https://editor.p5js.org/aa11972/full/b224cudrh