Concept

For this week’s assignment, my overall concept is pretty similar to the one I did last week because it also has something to do with sleep. This time, I created a light system: for the first one, I used a button to turn on a single LED manually, and for the second one, the yellow LED turns on when the lights are turned off, just like a night light! I got inspiration for this idea from my little sister when we were kids, because she always used to sleep with a night light on.

Code

int buttonPin = 8;

int greenLED = 7; // pin for green LED

int lightSensorPin = A2;

int yellowLED = 6; // pin for yellow LED

void setup() {

Serial.begin(9600);

pinMode(buttonPin, INPUT_PULLUP);

pinMode(greenLED, OUTPUT);

pinMode(yellowLED, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

int sensorValue = analogRead(lightSensorPin);

Serial.println(sensorValue); // prints sensor value from light sensor

if (digitalRead(buttonPin) == LOW) { // button pressed

digitalWrite(greenLED, HIGH);

} else {

digitalWrite(greenLED, LOW);

}

if (sensorValue < 175) {

digitalWrite(yellowLED, HIGH);

} else {

digitalWrite(yellowLED, LOW);

}

}

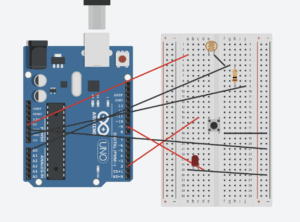

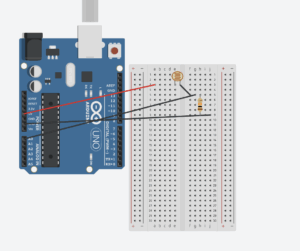

So basically, I used conditional statements for when I wanted each LED to turn on. The green LED was connected to the digital pins, so I used a button to turn it on and off: when the button is pressed, the LED lights up, and when it’s not pressed, the LED turns off. For the yellow LED, it checks the light sensor’s value, and when that value goes below 175, the LED turns on (so when the lights are off, the yellow LED acts as a night light!).

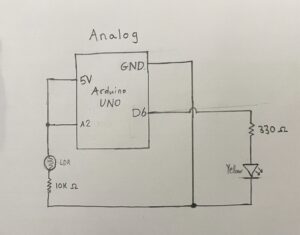

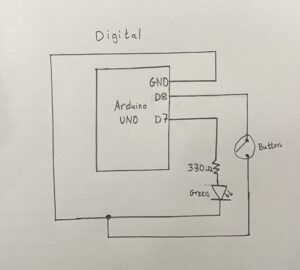

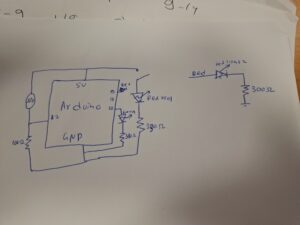

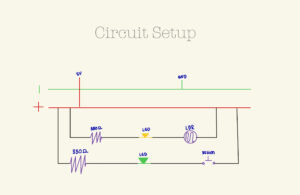

Hand-Drawn Schematic

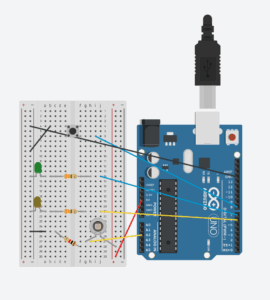

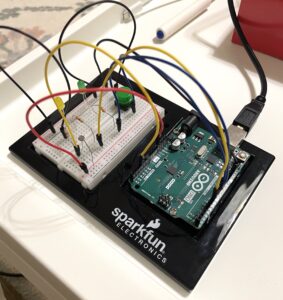

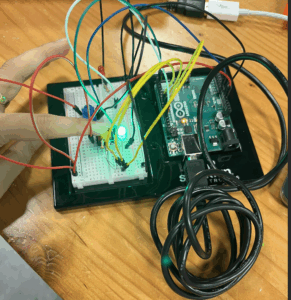

Schematic diagram and Photo:

Video Demo

Reflection and Future Improvements

Honestly, it was pretty hard to come up with a concept for this project, but when I did, I’m satisfied with how it turned out. Another thing was that I underestimated how much time this would take, it took me way too long to figure everything out and fix the issues on the circuit. In the future, I plan on practicing wiring more often and getting a better understanding of circuit logic.