Finalized Concept

For my final project, I’m building an interactive Spider-Man experience where you can “swing” around a simplified version of the NYUAD campus using a glove with a sensor in it. The glove basically becomes your controller, but in a way that feels way more like Spiderman. When you do the signature web shooting gesture, Spider-Man reacts instantly on screen. I Instead of clicking buttons or pressing keys, you just move your hand, and the game turns that motion into a web-shooting movement across the campus. The whole idea is to make it feel intuitive and fun, like you’re actually guiding him through the space instead of controlling him from a distance.

Hardware

I’m using a capacitive touch sensor to detect the Spider-Man web-shooting gesture. The sensor is placed on the palm of the glove, and the fingertips are left exposed so that when the player touches the sensor with the correct fingers, mimicking Spider-Man’s iconic “thwip” pose, the system registers a web shot. When the hand relaxes and the fingers release the sensor, the web disappears in p5.

The challenge is integrating the sensor onto the glove in a way that keeps it comfortable and responsive.

Arduino

The Arduino will:

-

- Continuously read values from the capacitive touch sensor on the glove’s palm

- Detect when the correct fingertips touch the sensor to register the Spider-Man web-shooting gesture

- Send a signal to p5.js via Serial whenever the web-shooting gesture is made or released

- Continuously read values from the capacitive touch sensor on the glove’s palm

This creates a one-way connection from the glove to the game, letting the hand gesture directly control Spider-Man’s web-shooting action in p5.js.

P5.js

-

- Receive the readings from Arduino

- Detect the web-shooting gesture to attach/release the web

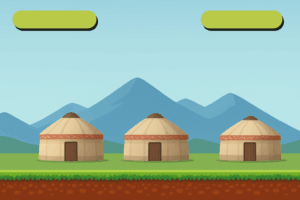

- Draw Spider-Man as a sprite moving across a simplified NYUAD campus

- Apply physics for swinging: gravity, momentum, web forces

Currently, the p5 prototype is in progress. I plan to make campus look like the setting of a playstation game, by putting pictures of campus and asking AI to game-ify.

Progress So Far

I have the basic structure of the Spider-Man glove game implemented in p5.js. This includes multiple screens (intro, instructions, game), a building with target points, and the beginning logic for shooting a web. Right now, the web-shooting gesture is simulated with the SPACE key, which triggers a web from Spider-Man to a random target for a short duration. The game is set up so that the Arduino input from the capacitive touch sensor can be integrated later to replace the key press.