Concept:

The idea behind my instrument was to create a hands-free musical device that transforms invisible gestures into sound. My goal was to design something playful yet technical; a device that reacts to both motion and touch. By combining distance and pressure, the instrument invites intuitive exploration: the closer your hand gets, the higher the note, while pressing the sensor triggers the sound. It merges tactile interaction with sound, making music a physical experience.

Method & Materials:

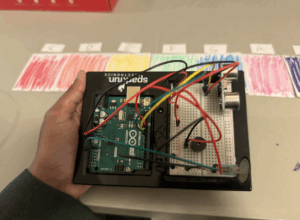

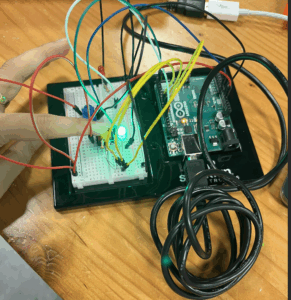

This project was my first time working with two types of sensors on the Arduino Uno:

- Analog Sensor: Ultrasonic sensor (HC-SR04) to measure distance.

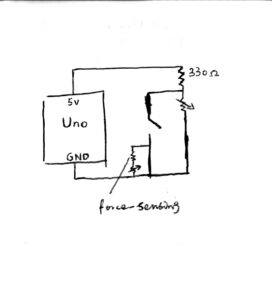

- Digital Switch: Force Sensitive Resistor (FSR) to detect pressure.

- Output: Piezo buzzer to produce sound.

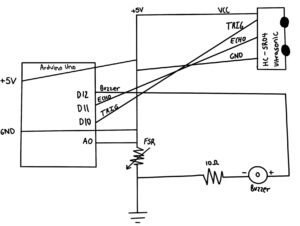

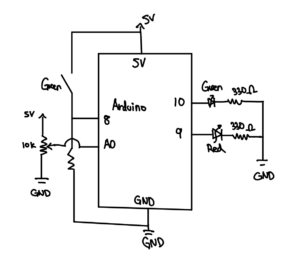

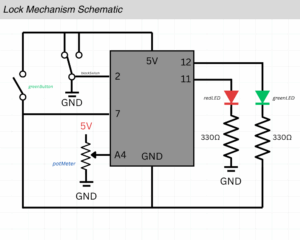

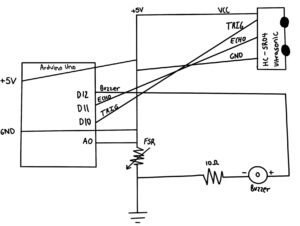

I connected the ultrasonic sensor to pins 10 (trig) and 11 (echo), the FSR to analog pin A0, and the buzzer to pin 12.

Each note from the C major scale (C–D–E–F–G–A–B) was assigned to a specific distance range, coded in an array:

int notes[7] = {261, 294, 329, 349, 392, 440, 494};

The system reads distance in real time:

- When the FSR is pressed and your hand is between 0–50 cm of the sensor, the buzzer plays a tone corresponding to that range.

- If no pressure is detected or the hand moves out of range, the sound stops.

Process:

At first, it took time to understand how analog vs. digital inputs work and how to read them simultaneously. I researched how to use pulseIn() for the ultrasonic sensor and experimented with mapping values using the map() function.

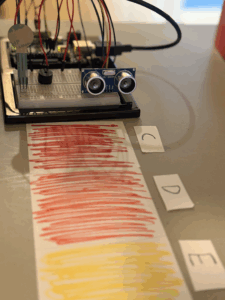

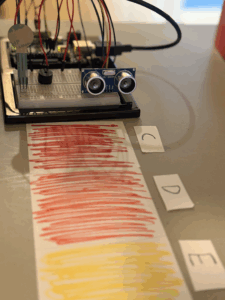

To visualize the notes, I placed colored paper strips at different distances (each representing one note of the scale)

Throughout the process, I learned:

- The importance of wiring correctly (e.g., ensuring the FSR forms a voltage divider).

- How combining two sensors can create more expressive interaction.

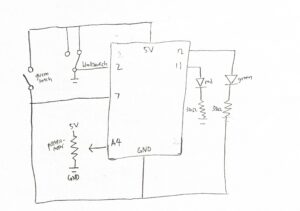

Schematic:

Code:

This combines input from two sensors, an ultrasonic sensor and a force-sensitive resistor (FSR) to generate musical notes through a piezo buzzer. The ultrasonic sensor continuously measures the distance of my hand, while the FSR detects when pressure is applied. When both conditions are met (hand within 50 cm and FSR pressed), the code maps the distance value to a specific note in the C major scale (C, D, E, F, G, A, B). Each distance range corresponds to a different pitch, allowing me to “play” melodies in the air. The code I’m most proud of is the single line that transforms the project from a simple sensor experiment into a musical instrument. It defines the C major scale, turning numerical frequency values into recognizable notes. I love that such a short line of code gives the device its expressive character, it bridges logic and creativity, translating distance data into melody. It’s the heart of the project, where sound and interaction truly come together.

// --- Define musical notes (C major scale) ---

int notes[7] = {261, 294, 329, 349, 392, 440, 494}; // C D E F G A B

Result:

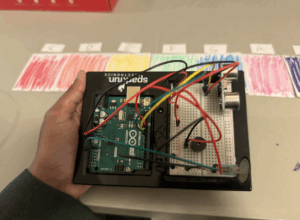

The final prototype acts like an invisible piano: you play by waving your hand in front of the sensor and pressing lightly on the FSR. Each distance triggers a different musical note. The colored papers made it easier to perform intentionally and visually mark pitch changes.

In the demonstration video, the tones respond smoothly to my gestures, transforming simple components into an expressive interface.

Challenges:

One of the main challenges I faced was understanding how each pin on the ultrasonic sensor worked. At first, I didn’t realize that every pin had a specific purpose, like trig for sending signals and echo for receiving them, so it took me a while to fully grasp how data was actually being measured. I also struggled with wiring the circuit, often making small mistakes that stopped the whole setup from working. Drawing out the schematic was another time-consuming part since there were many components to connect and label correctly. Finally, the coding process was challenging because it was my first time using several of these elements, and I had to learn through trial and error how to make the sensors and buzzer communicate smoothly.

Inspiration + Tools thats helped me:

https://projecthub.arduino.cc/theriveroars/simple-hand-controlled-instrument-372bfc

https://learn.adafruit.com/force-sensitive-resistor-fsr/using-an-fsr

Reflection:

This project taught me how code, sensors, and sound can merge into interactive art. The challenge was balancing sensitivity: sometimes the ultrasonic readings fluctuated, and it took some fine tuning. But once it worked, it felt rewarding to hear the instrument. It also made me realize how music can be built from logic, how creative coding allows emotional expression through electronics. I see this as the beginning of exploring computational instruments that combine art and technology.