Inspiration:

When I was younger, I loved buying small packets of seeds and trying to grow different flowers, even though most of them never survived in the dry soil of the UAE. I remember checking on them every day and watering them, moving them around for sunlight, and hoping each time that a sprout would appear. Even though many of these attempts failed, the process itself was exciting, and it sparked a fascination with plants that stayed with me. The Plant Care Station grew directly from that childhood experience: it is my way of recreating the joy, curiosity, and trial-and-error learning that I felt when I tried to care for real plants.

Concept

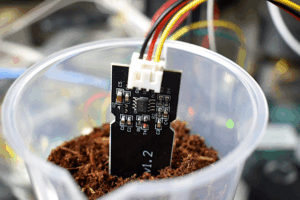

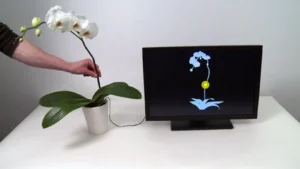

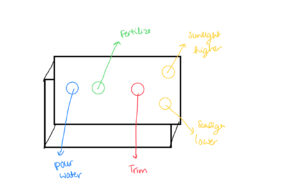

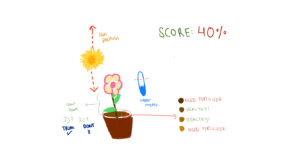

The Plant Care Station, is an interactive experience that allows users to experience the basic steps of caring for a plant using arduino sensors and creative digital feedback through p5. The concept blends physical interaction with a digital narrative. For instance, users provide sunlight, water, fertilizers and leaf maintenance to a virtual plant by triggering corresponding sensors in the physical setup. Light sensors respond to flashes of brightness, a moisture sensor detects watering actions, and a capacitive sensor tracks leaf trimming. Each successful step of taking care of the plant advances the user through a series of stages, visually reflecting the plant’s growth and wellbeing. The goal of the concept is to make plant care feel engaging, intuitive, and educational by transforming everyday actions into an interactive journey.

Implementation: Interaction Design

The interaction design of my project mainly involves elements of p5.js that responds directly to sensor input (digital and analog) from the Arduino. Each stage from sunlight, watering, to leaf-trimming has its own visual environment and logic, and the user’s physical actions with the sensors determine how the the sketch moves forward.

The light sensors trigger progression when the brightness crosses a defined threshold, making the sun figures appear larger and brighter in the p5 program. The moisture sensor stops updating once the soil reaches the required moisture level, based on our defined threshold that was set during testing. Lastly, the capacitive sensor on both sides of the scissors detects transitions from “NO_TOUCH” to “TOUCH” to count how many leaves the user has pruned. This design ensures that the interaction feels responsive and purposeful.

Arduino Code:

#include <CapacitiveSensor.h> // we are using the CapacitiveSensor library so we can use capacitive touch sensing this is measuring changes in capacitance

CapacitiveSensor capSensor = CapacitiveSensor(8, 7); // here we make the cap sensor object whic uses pins 8 and 7 ans the send and recieve pins

const int TOUCH_PIN = 2;// this is the pin which we have the foil touch connected

const int ledPins[4] = {12, 11, 10, 13}; // these are all the pins we have dedictedm for the leds

bool partyMode = false; //party mode is set for the order in which the leds are lit

int currentLED = 0; //index of the current led starts from 0 ends at 3

int waveDirection = 1; // wave direction varaible alternates between 1 and -1 for the order in which the leds wave is lit

unsigned long lastUpdate = 0; //stores the last time the leds were updated

const int waveInterval = 30; // adjust to 20 for fast led change

void setup() {

Serial.begin(9600); //settung the serial connection at 9600 baud so ard can talk to p5

pinMode(TOUCH_PIN, INPUT_PULLUP); // this allows for the conductive contact: when touched- reads HIGH when not reads LOW

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {//looping over all the led light

pinMode(ledPins[i], OUTPUT);

digitalWrite(ledPins[i], LOW); //turn off initialluy

}

}

void loop() {

int soil = analogRead(A4); delay(2); // for the soil moisture senor

int a0 = analogRead(A0); delay(2); // light sensors

int a1 = analogRead(A1); delay(2);//light sensors

int a2 = analogRead(A2); delay(2);//light sensors

int a3 = analogRead(A3); delay(2);//light sensors

long capValue = capSensor.capacitiveSensor(30); //number of samples set to 30, after testing found this was the best value that did not compromise the speed and had good enough accuracy

bool touched = (digitalRead(TOUCH_PIN) == LOW); //reading of digital pin 2 LOW--> baiscally indicated contact

//send all readings to Serial for p5

Serial.print(soil); Serial.print(",");

Serial.print(a0); Serial.print(",");

Serial.print(a1); Serial.print(",");

Serial.print(a2); Serial.print(",");

Serial.print(a3); Serial.print(",");

Serial.print(capValue); Serial.print(",");

Serial.println(touched ? "TOUCH" : "NO_TOUCH");

//here we listen for commands from P5

if (Serial.available()) {

String cmd = Serial.readStringUntil('\n'); //check for incoming data stop when you find a new line

cmd.trim();//break there

if (cmd == "LED_ON") { //we send this from p5 when we reached the last page

partyMode = true; //turn party mode on for leds

currentLED = 0;

waveDirection = 1;// move leds on from left to right

}

else if (cmd == "LED_OFF") {

partyMode = false;//turn party mode off for leds

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) digitalWrite(ledPins[i], LOW);//one by one

}

}

if (partyMode) { //light turning on order

unsigned long now = millis();

const int blinkInterval = 120; // adjust speed here

if (now - lastUpdate >= blinkInterval) { //checking the time intervals beywen leds lit

static bool ledsOn = false; //in every blinkInterval we toggle whether leds should be on or of

ledsOn = !ledsOn; // toggle on to off

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {//loops through all 4 LEDs

digitalWrite(ledPins[i], ledsOn ? HIGH : LOW); //true set high false set low

}

lastUpdate = now; //refresh the last updated time fpr the next toggle

}

}

delay(5);

}

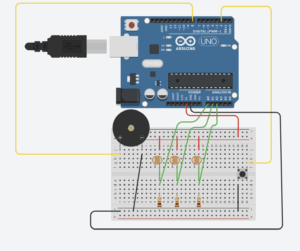

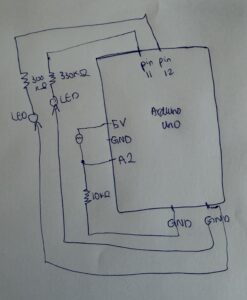

Description and Main functionalities: My Arduino program combines multiple sensors (analog and digital) and LED effects to communicate with a p5.js sketch and create interactive plant care visuals. It uses the CapacitiveSensor library to detect touch through changes in capacitance , while a separate foil touch sensor on pin 2 provides a simple digital touch reading. Four LEDs connected to pins 12, 11, 10, and 13 are controlled through a party mode system that makes them blink together when triggered by p5.js. In the main loop, the Arduino continuously reads data from the soil moisture sensor (A4), four light sensors (A0–A3), the capacitive touch sensor, and the foil touch input. All these sensor values are then sent over Serial at 9600 baud to p5.js in a comma-separated format- which was helpful for debugging especially with the soil moisture sensor when the wires would come off. The code also listens for incoming Serial commands from p5, such as our ending LED-ON which activates party mode, causing all LEDs to flash on and off . A small delay at the end stabilizes the sensor readings and controls the noise.

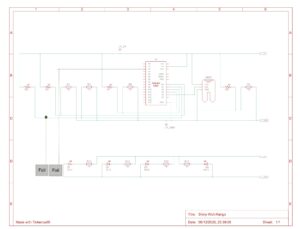

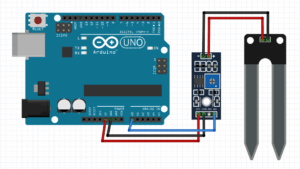

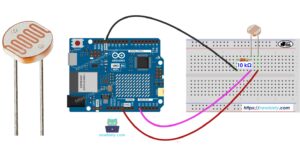

Schematic:

P5 Description:

1. Serial Communication & Sensor Integration

The p5.js sketch’s main logic that makes this game interactive is built around serial communication with the Arduino. The sketch kind of acts as the visual and interactive front-end for plant-care data. For every frame the program checks whether the serial port is open, reads a full line of comma-separated values, and parses seven different sensor readings: soil moisture, four light sensors, a capacitive sensor, and the foil touch state. These values drive the logic of each game stage from light balancing to watering and pruning. The code also sends signals back to the Arduino using simple text commands such as “LED_ON”, “LED_OFF” allowing the arduino side(specifically the LED) to respond to the user’s progress. This bidirectional setup makes the interface feel alive, creating a tight feedback loop between the digital visuals and real environmental interactions.

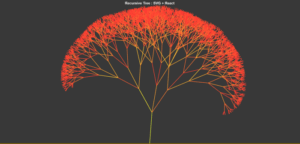

2. Recursive Tree System (Inspired by Decoding Nature Lectures)

A major visual element of my p5 sketch is a dynamic, recursive tree -inspired directly by concepts from the Decoding Nature course lectures. Each game page grows to a more mature tree configuration, by changing trunk thickness, branch angles, branch scaling, blossom density, and root structure. The trees are generated using a recursive branching function that draws a segment, translates upward, and then splits into multiple smaller branches with subtle randomness. The result is a nature-inspired visualization built from mathematical rules, but artistically tuned to feel alive and expressive.

3. Additional Interactive & UI Features

Beyond the analog and digital sensors and trees, the sketch builds a complete game like some functions that make animated text, responsive buttons, confetti celebrations, and stage-based UI transitions. Each page has its own layout, and unified design for the buttons, and a modern interface with moving characters for the titles. The bouncing text titles adds a playful touch. The sketch also has an input field that allow the user to specify how many leaves they expect to prune- by observing the darker color leaves. Confetti bursts appear when a light sensor zone is completed, rewarding the user visually and allowing them to move to the next round. Throughout the experience, actions like watering, pruning, and finishing a session are tied to both sensor readings and visual transitions, giving users a feeling of caring for a plant step by step, both physically and digitally.

Embedded Sketch:

Communication Between Arduino and P5:

The communication between the Arduino and p5.js begins as soon as the sketch loads. This is when p5 creates a serial port object and tries to open the port at a baud rate of 9600. Once the port is open, p5 continuously listens for incoming data in the draw loop. The Arduino in return sends a full line of comma-separated sensor values: soil moisture, four light readings, capacitive value, and foil-touch state. This is then read by p5 using the readuntil where we stop at /n for new lines. It then updates into its variables each frame. As the user interacts with the interface, p5 interprets these sensor values to move the game logic forward and visuals, such as lighting suns, filling the soil bar, or counting pruning events. Communication also flows in the opposite direction: when the user reaches certain milestones for exaple like completing the session, p5 will send back the commands to Arduino using port.write , such as “LED-ON” and trigger celebratory LED behavior. This back-and-forth loop of sending sensor data from Arduino and sending commands from p5 creates a synchronized, interactive experience tightly linking physical actions with digital responses.

Parts I am Particularly Proud of:

At the start of the project, I had no experience working with sensors like the the soil moisture sensor, so even understanding their raw readings felt overwhelming. I didn’t know how to interpret the values, how to calibrate them, or how to integrate them into meaningful interactions. Through tutorials, schematics, documentation, and simple testing sketches, I gradually learned how each sensor behaved and what its data actually meant. This process helped me understand how to map their values into thresholds, smooth out noise, and ultimately use them confidently within my project.

I am also particularly proud of the physical design work . Using the laser cutter, I built a wooden enclosure for the plants and the tools(scissors, water and flash light). This was my first time designing designing something like this, and learning how to convert a digital sketch into precise vector cuts was incredibly rewarding. In addition, I used Tinkercad and the 3D printer to design small globe pieces that sit over the LEDs and act as tiny diffusers, creating a fun disco-style glowing effect during the celebration mode. These handmade physical elements added personality to the project and made the final interaction feel more polished and playful.

Struggles:

One major challenge was scaling the interaction by switching from an Arduino Uno to an Arduino Mega so I could add more sensors, such as piezo inputs, but the process was difficult, and I accidentally burned the Mega while troubleshooting wiring. Another struggle came from the fabrication side: when designing LED covers, the 3D printer malfunctioned and could only produce partial hemispheres instead of full spheres, which limited the effect I originally envisioned. These setbacks were frustrating in the moment, but they pushed me to adapt quickly, rethink my design choices, and find creative workarounds.

Areas of Future Improvement:

I also used AI (ChatGPT) in two key ways: first, to refine the visual design of the interface by helping me choose cohesive color schemes and polished button styling; and second, to analyze batches of raw sensor readings from the serial monitor so I could determine reliable thresholds for light, moisture, and touch detection. These tools and references collectively helped shape the final project, balancing hands-on experimentation with guided learning.

Here’s an example of what those blocks of code look like:

function styleLeafInput(inp) {

inp.style("padding", "10px 14px"); // inner spacing for comfortable typing (chatgpt design choice)

inp.style("font-size", "18px"); // readable font size

inp.style("border-radius", "999px"); // pill-shaped rounded input (chatgpt styling suggestion)

inp.style("border", "2px solid " + COLOR_ACCENT_SOFT); // soft accent border for aesthetic consistency

inp.style("outline", "none"); // removes default browser outline

inp.style("font-family", "Poppins, Arial, sans-serif"); // clean modern font (chatgpt ui recommendation)

inp.style("box-shadow", "0 3px 10px rgba(136, 182, 155, 0.35)"); // subtle shadow for depth (chatgpt design touch)

inp.style("background-color", "#FFFFFF"); // white background for high readability

inp.style("color", COLOR_TEXT_DARK); // dark text for good contrast

}

Or such as these color schemes:

stroke("#6B5032");

drawingContext.shadowColor = "rgba(245, 210, 110, 0.8)";