For my final project, I will create a physically interactive Tamagotchi. It is a mini robot creature that the user can pat, touch, spin, and talk to, but instead of being cute and grateful, it responds in unexpectedly pessimistic and slightly hostile ways. The project combines physical interaction through Arduino sensors with a character interface and dialogue system in p5. The concept is inspired by classic Tamagotchi toys, small handheld digital pets that demand constant attention and reward care with affection. In contrast, my project imagines a near-future world in which artificial beings no longer need, or even want, human caretaking. This pet has a personality shaped by human environmental destruction and techno-optimism gone wrong, and it is deeply unimpressed by humans.

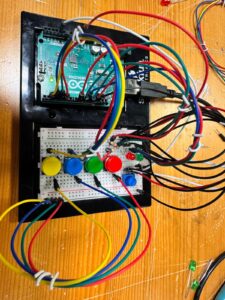

Physically, the project will take the form of a small creature-like object mounted on a potentiometer so that the whole robot can be spun like a tiny rotating idol. The main interactions happen through touch and rotation. The user can pat or press the creature via a force sensor embedded in its body, and they can spin it to face different directions using the potentiometer as a rotation input. Inside the body, the creature uses NeoPixels to show changing emotions through light patterns, while on the computer a p5 interface displays a larger animated avatar of the creature and shows its dialogue text.

Unlike typical virtual pets that reward attention with affection and gratitude, this creature is intentionally negative and resistant. When the user pats it, it might snap: “Go away, you silly little human.” When the user spins it so that it faces away, it might respond: “Correct. I prefer not to see you.” If the user keeps spinning it quickly, the creature may complain: “Dizzy. This is abuse, not affection.” When the robot is left facing a corner with its back turned to the user, it may mutter: “Finally. A view without humans in it.” The rotation angle therefore becomes a key part of the interaction design. Different angular positions correspond to different stances or modes of the creature, and those modes drive both the NeoPixel emotion effects on the physical object and the dialogue responses on the p5 screen.

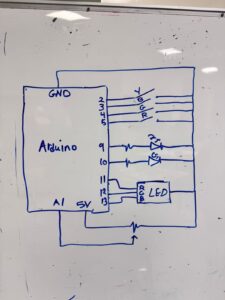

On the Arduino side, the project relies on two main inputs that are sent to p5 over serial communication. The first is a force sensor used as a pat or squeeze input. The Arduino continuously reads the analog value from the FSR, maps the raw reading to a smaller range such as 0 to 10 representing pat intensity, and sends this information to p5 in the form of tagged serial messages like “PAT:<value>”. A reading of “PAT:0” would mean no touch, while something like “PAT:9” would correspond to an aggressive squeeze. The second input is the potentiometer that encodes the robot’s rotation angle. The creature is physically attached to the shaft of the potentiometer so that when the user spins the creature, they are directly rotating the pot. The Arduino reads the analog value from the potentiometer, originally in the range 0 to 1023, and maps it either to a normalized angle between 0 and 359 degrees or to a set of discrete orientation zones. For example, Zone 0 can represent facing the user, Zone 1 slightly turned to the left, Zone 2 slightly turned to the right, and Zone 3 completely turned away with its back to the user. The Arduino then sends periodic messages to p5 such as “ANGLE:<value>” for the continuous angle or “ZONE:<id>” for the discrete orientation. As a stretch feature, the Arduino can also compare the current angle with the previous reading to estimate spin speed and send additional messages such as “SPIN:FAST” or “SPIN:SLOW” if there is enough time to implement this.

The Arduino is also in charge of several outputs, primarily the NeoPixels that visualize the creature’s emotional state. The NeoPixels are used to display different moods and orientations through color and animation patterns. The Arduino listens for commands coming from p5, such as “MOOD:ANGRY”, “MOOD:BORED”, “MOOD:AMUSED” or “MOOD:DISGUSTED”, and possibly additional tags like “DIR:FRONT”, “DIR:LEFT”, “DIR:RIGHT” and “DIR:BACK” that encode the direction it should appear to be facing. For each combination of mood and orientation, the Arduino selects a specific pattern from a small internal lookup table of NeoPixel animations. For instance, when the creature is facing the user and annoyed, the LEDs might show sharp, high-contrast flashing patterns. When it is turned away, the colors might become dim and cold to signal that it is ignoring the user. When the user spins it quickly, it might display chaotic, flickering lights to suggest dizziness and disturbance. In this way, the Arduino acts as the body-level controller that turns high-level mood messages from p5 into concrete light and motion behaviors on the physical pet.

On the p5 side, the program handles visual behavior, dialogue, and integration of the serial data coming from Arduino. The main visual element is a two-dimensional avatar of the creature whose orientation mirrors the potentiometer readings. When Arduino reports that the creature is in Zone 0, facing the user, the avatar will be drawn facing forward. When it reports Zone 1 or Zone 2, the avatar will turn slightly left or right. When it reports Zone 3, the avatar will show its back or a dismissive side profile. Background layers or subtle interface elements can reinforce the sense of orientation, for example by using a spotlight effect when the creature faces the user, and a shadowy or desaturated background when it turns away.

The p5 sketch keeps track of several state variables. It records the current orientation zone or angle reported by Arduino, the most recent pat intensity from the “PAT:<value>” messages, and the time since the last interaction to detect whether the user is ignoring the creature or constantly bothering it. Based on these values, p5 chooses a mood state such as “Annoyed”, “Dizzy”, “Dismissive” or “Begrudgingly Attentive”. That mood state determines the avatar’s expression, including eyes, mouth shape, and posture, as well as background color or small motion effects like shaking or pulsing. Whenever the mood changes, p5 also sends the corresponding mood label back to the Arduino, for example “MOOD:DISMISSIVE”, so the NeoPixels can stay synchronized with the on-screen visuals.

Dialogue and personality are deeply connected to rotation and touch. p5 interprets the angle or orientation zone in semantic terms. When the creature is facing the user in Zone 0, it selects lines that complain about being watched, such as “Why are you staring? I do not perform on command.” When it is turned slightly away in Zones 1 or 2, it may comment on the user’s persistence with lines like “You still there? Unfortunately, yes.” When it is turned completely away in Zone 3, it chooses more extreme dismissive phrases such as “This direction is better. Less human.” If the system detects fast spinning, it can draw from a set of dizzy or abused responses like “Stop spinning me. I am not a fidget toy.”

Beyond instantaneous input, p5 maintains some simple memory over time. It tracks how often and how strongly the creature has been patted in the recent past and how often the user has spun it back and forth between zones. By combining rotation data with touch data, the system can generate interaction-dependent responses. For example, if the user keeps forcing the creature to face them by repeatedly moving it back into Zone 0 after it has “chosen” to be in Zone 3, the creature can complain about humans forcing attention with lines such as “You keep dragging me back. Typical human behavior.” If the user spins it away and then leaves it alone for a while, the system can trigger more subtle, relieved comments like “Finally. A horizon without you.”

The dialogue itself will at minimum be based on prewritten arrays of lines for each mood and orientation combination. p5 will maintain collections such as “linesFacingAnnoyed”, “linesBackTurned” or “linesDizzy” and will choose one line depending on the current mood, orientation zone, and a bit of randomness, to avoid sounding too repetitive. As a stretch goal, the project may integrate an AI API into p5. In that case, p5 would send a short prompt that includes the current mood, orientation description (such as “facing”, “back turned”, “spun fast”), and a brief summary of recent interactions. It would then receive a generated line of dialogue and optionally wrap or filter it to ensure it remains safe, in character, and consistent with the theme. In both the base and stretch versions, the personality remains negative, sarcastic, and skeptical of humans, reflecting a world where artificial beings are not necessarily grateful for their existence or their relationship with their creators.