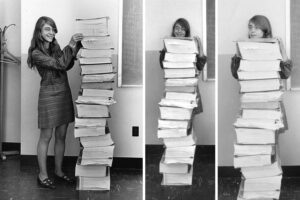

It’s revolutionary to see the scale of what Margaret Hamilton achieved. She didn’t just break gender stereotypes, she essentially founded an entire discipline that grew into a billion-dollar industry: software engineering. While we all remember Neil Armstrong as the first man to step on the moon, we rarely think about the person who made that step possible. Reading about Hamilton made me realise how much unseen effort lies behind every historic moment.

As a woman in computer science, a field still largely dominated by men, her story feels deeply personal and inspiring. It’s empowering to see someone who not only challenged norms but also redefined “engineering.”

One part of the reading that resonated with me on a technical level was Hamilton’s insistence on anticipating and handling errors. When I first started learning to code, I used to find “try,” “except,” and “catch error” statements frustrating and unnecessary. I would think, why not just tell users not to make mistakes? But Hamilton’s experience showed the flaw in that thinking. Even an astronaut, among the most trained and intelligent individuals, made an oversight that could have led to mission failure. That moment completely reframed my understanding: robust systems are not built on the assumption that people won’t perform error, but on the expectation that they inevitably will.

This reading reminded me that testing, error handling, and designing for failure are not tedious parts of coding, they’re acts of responsibility and necessity. Margaret Hamilton’s story shows that great engineering is not just about writing functional code but about preventing failure, protecting people, and thinking ahead. It’s a mindset I want to carry into every project I work on.