Concept

I started the brainstorming of generative text art by the inspiration of Tibetan font we’ve seen in class. I felt so amazing how this niche and complicated language can be incorporated into unicode and redesigned into various new format. Then I came up the idea of generating rearrangement of typography from Chinese Wubi input method, which decomposes characters into strokes that can then be recombined into full forms. I wanted to apply this same principle of decomposition and recomposition to my favorite language of all times: Nüshu (The direct shortcut key for ü is v, referring as Nvshu in the following).

Nvshu was historically used in Jiangyong County, Hunan, China, as a secretive women’s writing system. It is the only known script in the world designed and used exclusively by women, and was transmitted through sisterhood groups, generational teaching, and playful exchanges. Today, Nvshu often appears on carvings, embroidered fans, handbags, or even tattoos, celebrated as both a form of sisterhood heritage and an aesthetic design language.

My goal was to design a digital generative “Nvshu board” where users can appreciate the beauty of these glyphs and play with them (dragging, rearranging, and composing their own patterns). The resulting forms resemble ornaments, motifs, or even tattoo-like compositions, highlighting how a script can carry both linguistic and visual meaning.

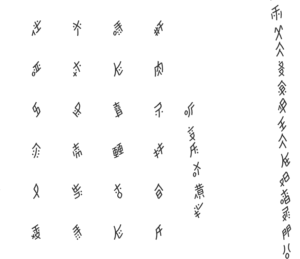

Sketch (Written Horizontally, same as historical Chinese Characters)

Highlight Code

The code I am most proud of is the section that generates random Nvshu glyphs from the Unicode range and places them into a 10×10 board. To make sure the characters display properly, I had to research Unicode code points and how to convert them into visible strings in p5.js. The line below is the most rewarding part of my code:

// randomized and round down to integer to match the string

let nscode = floor(random(0x1B170, 0x1B2FB + 1));

//take the code create the string from the unicode sequence of code points

// saw this way of locating unicode in chinese-fonts p5.js works by tytyshi

let nsglyph = String.fromCodePoint(nscode);

// store it into the array with parameters

Here, random() generates a floating-point number within the Unicode range for Nvshu (0x1B170 to 0x1B2FB inclusive). floor() ensures the result is an integer, since Unicode code points must be whole numbers. Then, String.fromCodePoint() converts that integer into the actual Nvshu glyph. This was a breakthrough moment for me, because it connected abstract Unicode numbers to visible characters and allowed me to fill the canvas with living Nvshu script.

On top of this, I added drag-and-drop interactivity: when the user presses a glyph, the program tracks it and updates its coordinates as the mouse moves. This simple interaction lets users create their own custom compositions from the script.

Future Improvements and Problems

While researching fonts, I first discovered a brush-style Nvshu font package on GitHub. However, its size (18.3MB) exceeded the 5MB upload limit on the p5.js online editor. This led me to the only option of Noto Sans Nvshu on Google fonts. This size of 0.2MB really surprised me. Learning this powerfulness of unifying typeface made me think about how technology preserves cultural memory. I also consulted Lisa Huang’s design reflections on the challenges of Noto Sans Nüshu (https://www.lisahuang.work/noto-sans-nueshu-type-design-with-multiple-unknowns) to better understand the typographic logic of the font.

I would also like to add a save feature in future, so that once users have composed a design, they could export it as an image (to use as a print, tattoo design, or ornament).

This project combined cultural research, typographic exploration, and interactive coding. By bringing Nvshu into a playful digital space, I wanted to highlight both its fragility as an endangered script and its resilience through Unicode and modern typography. Users can engage with scripts not only as carriers of language but also as visual and cultural materials.