For this assignment, I had a hard time coming up with a creative idea. My twin nephews were over at the time, and I could hear them arguing about something. When I checked up on them, they were fighting over whoever was faster than the other, so I decided to make something to settle that (Love you, Ahmed and Jassim).

The concept is pretty simple:

It’s a two-player game. One player gets the photoreceptor, and the other gets the button. Whoever can cause their light to flash first proves that they’re faster than the other.

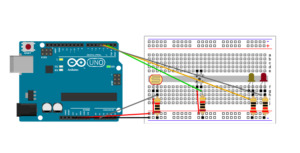

Materials Used:

- 2x 330 resistors

- 2x 10k resistors

- 8x wires

- 2x LEDs (one Red, one Yellow)

- 1x button

- 1x photoresistor

Setup:

I used examples from previous classes to piggyback on. The slides were very helpful to me.

The website I used will NOT be used again. Although I faced many problems with the resistors, it got the job done.

Code:

int photoSensorPin = A1;

int buttonPin = 2;

int ledPin1 = 3;

int ledPin2 = 4;

void setup() {

pinMode(photoSensorPin, INPUT);

pinMode(buttonPin, INPUT);

pinMode(ledPin1, OUTPUT);

pinMode(ledPin2, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

int sensorValue = analogRead(photoSensorPin);

int buttonState = digitalRead(buttonPin);

if (buttonState == HIGH) {

digitalWrite(ledPin1, LOW);

digitalWrite(ledPin2, HIGH);

} else if (sensorValue < 450) {

digitalWrite(ledPin1, HIGH);

digitalWrite(ledPin2, LOW);

} else {

digitalWrite(ledPin1, LOW);

digitalWrite(ledPin2, LOW);

}

}

Demo:

Reflection:

Making this game was a pretty fun challenge for me. This language is very new to me, and I’m still having issues getting used to it. I would like to take this a step further and possibly use other forms of input devices to accurately guess who’s faster (Ahmed won BTW).