Concept

I was thinking long and hard about the final project that would be a great finale to all of the things we have learned during the semester. I have decided I want to make a robot. Robot is a broad term and I had to decide the purpose of mine, and since I wanted to create something that is innovative, fun and creative I decided to make a maze solving robot. The initial plans were to make the robot go through the maze on its own and have the user just set up the maze, but we will get to why it didn’t work out like that later. Instead of the robot solving the maze on its own, now its the user who is in control and trying to go through it “blind”, precisely using the ultrasonic sensors as guides. The user that controls the robot does not see the maze and is solving it based just on the sensors, while their friend rearranges the maze between sessions in order to make the game fun and interesting throughout the session.

Video of user interaction with the project

Arduino code

const int AIN1 = 13;

const int AIN2 = 12;

const int PWMA = 11;

const int PWMB = 10;

const int BIN2 = 9;

const int BIN1 = 8;

const int trigPinFront = 6;

const int echoPinFront = 5;

const int trigPinLeft = A0;

const int echoPinLeft = 2;

const int trigPinRight = 4;

const int echoPinRight = 3;

unsigned long lastEchoTime = 0;

const unsigned long echoInterval = 300;

void setup() {

Serial.begin(9600);

pinMode(AIN1, OUTPUT);

pinMode(AIN2, OUTPUT);

pinMode(PWMA, OUTPUT);

pinMode(BIN1, OUTPUT);

pinMode(BIN2, OUTPUT);

pinMode(PWMB, OUTPUT);

pinMode(trigPinFront, OUTPUT);

pinMode(echoPinFront, INPUT);

pinMode(trigPinLeft, OUTPUT);

pinMode(echoPinLeft, INPUT);

pinMode(trigPinRight, OUTPUT);

pinMode(echoPinRight, INPUT);

Serial.println("READY");

}

void loop() {

if (Serial.available()) {

char command = Serial.read();

//Resppond to command to move the robot

switch (command) {

case 'F':

leftMotor(50); rightMotor(-50);

delay(1000);

leftMotor(0); rightMotor(0);

break;

case 'B':

leftMotor(-50); rightMotor(50);

delay(1000);

leftMotor(0); rightMotor(0);

break;

case 'L':

leftMotor(200); rightMotor(200);

delay(300);

leftMotor(200); rightMotor(200);

delay(300);

leftMotor(0); rightMotor(0);

break;

case 'R':

leftMotor(-200); rightMotor(-200);

delay(300);

leftMotor(-200); rightMotor(-200);

delay(300);

leftMotor(0); rightMotor(0);

break;

case 'S':

leftMotor(0); rightMotor(0);

break;

}

}

//Send distance data to the serial

unsigned long currentTime = millis();

if (currentTime - lastEchoTime > echoInterval) {

float front = getDistance(trigPinFront, echoPinFront);

float left = getDistance(trigPinLeft, echoPinLeft);

float right = getDistance(trigPinRight, echoPinRight);

Serial.print("ECHO,F,"); Serial.println(front);

Serial.print("ECHO,L,"); Serial.println(left);

Serial.print("ECHO,R,"); Serial.println(right);

lastEchoTime = currentTime;

}

}

//Logic for controling the movement of the right and left motor

void rightMotor(int motorSpeed) {

if (motorSpeed > 0) {

digitalWrite(AIN1, HIGH);

digitalWrite(AIN2, LOW);

} else if (motorSpeed < 0) {

digitalWrite(AIN1, LOW);

digitalWrite(AIN2, HIGH);

} else {

digitalWrite(AIN1, LOW);

digitalWrite(AIN2, LOW);

}

analogWrite(PWMA, abs(motorSpeed));

}

void leftMotor(int motorSpeed) {

if (motorSpeed > 0) {

digitalWrite(BIN1, HIGH);

digitalWrite(BIN2, LOW);

} else if (motorSpeed < 0) {

digitalWrite(BIN1, LOW);

digitalWrite(BIN2, HIGH);

} else {

digitalWrite(BIN1, LOW);

digitalWrite(BIN2, LOW);

}

analogWrite(PWMB, abs(motorSpeed));

}

//Logic for measuring distance

float getDistance(int trigPin, int echoPin) {

digitalWrite(trigPin, LOW);

delayMicroseconds(2);

digitalWrite(trigPin, HIGH);

delayMicroseconds(10);

digitalWrite(trigPin, LOW);

long duration = pulseIn(echoPin, HIGH);

float distance = duration / 148.0;

return distance;

}

The Arduinos main purpose is to handle motor move meant as well as use the data from the distance sensors and send them to p5. For the movement it takes data from p5 which the user enters by pressing buttons on the keyboard and translates them to motor movement which imitates the movement on screen. The data from the 3 ultrasonic sensors is picked up with the Arduino and sent to the serial in order to be picked up by p5.

The p5 code takes the echo values that the Arduino sends and uses that date to draw the “echo lines” which the user will use to “see” the maze with the walls being visible every now and then if in range. P5 is also used to take user input and send it to the Arduino which translates it to movement. It also has code that serves as main connection from the Arduino to p5.

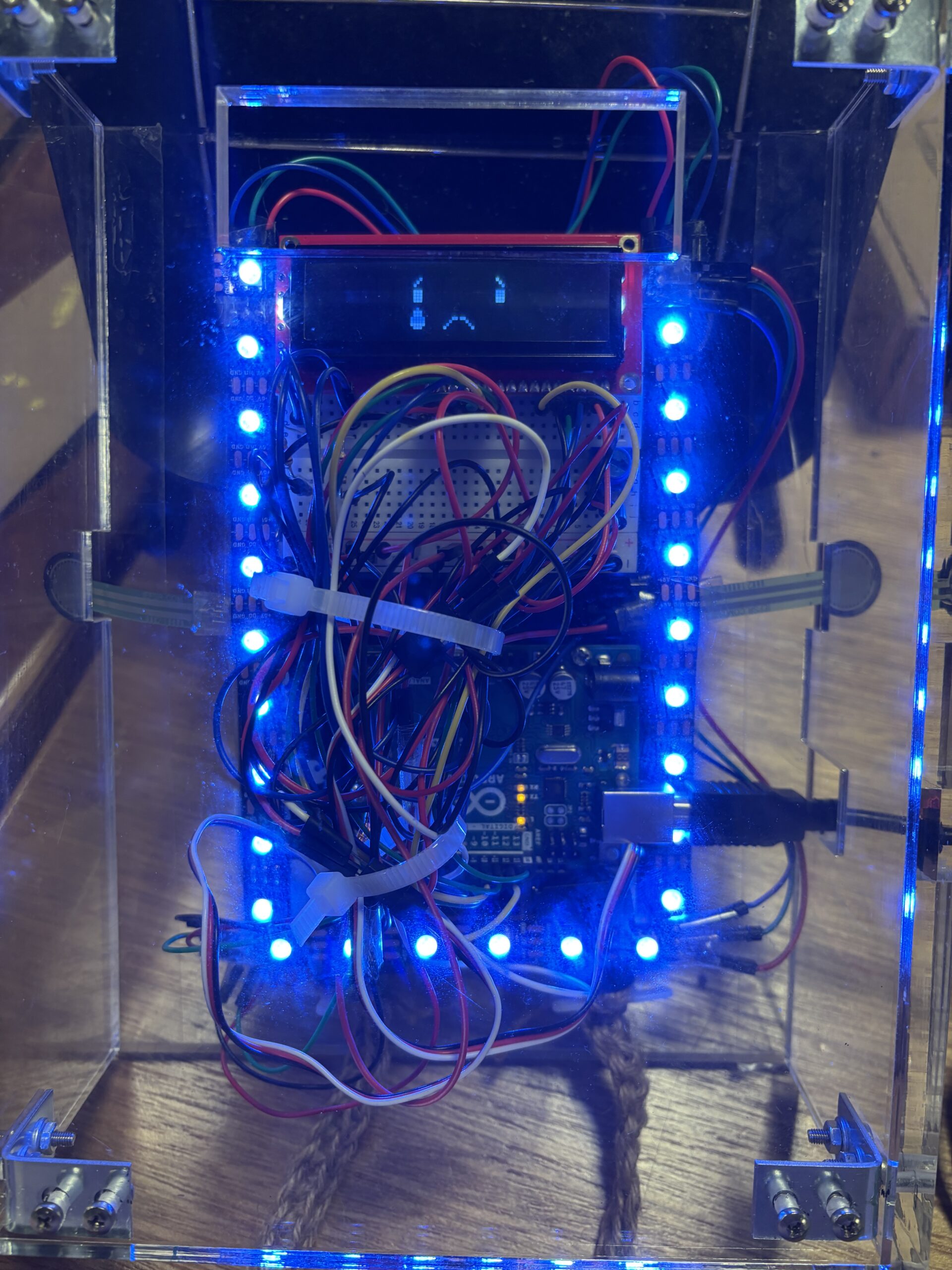

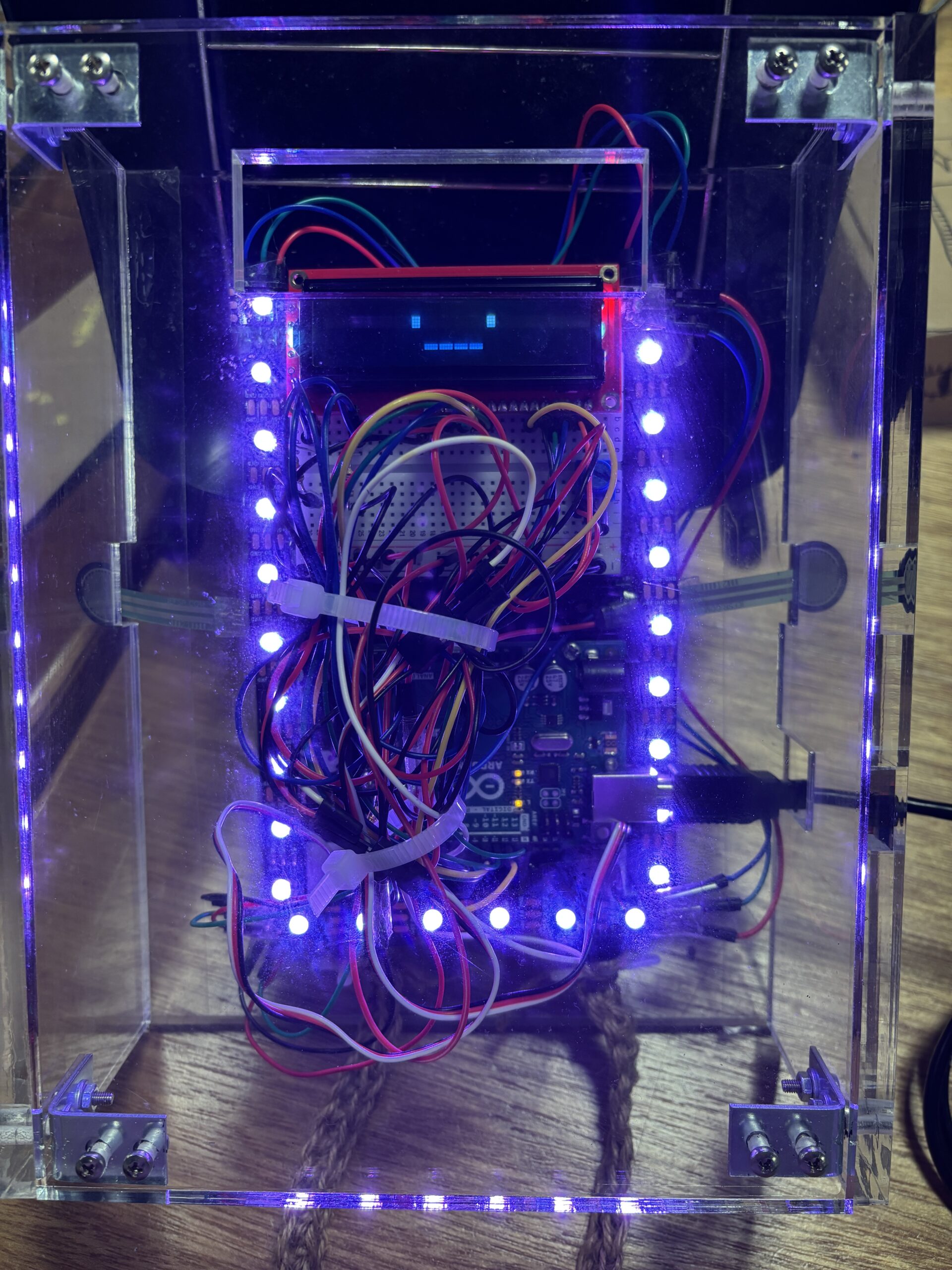

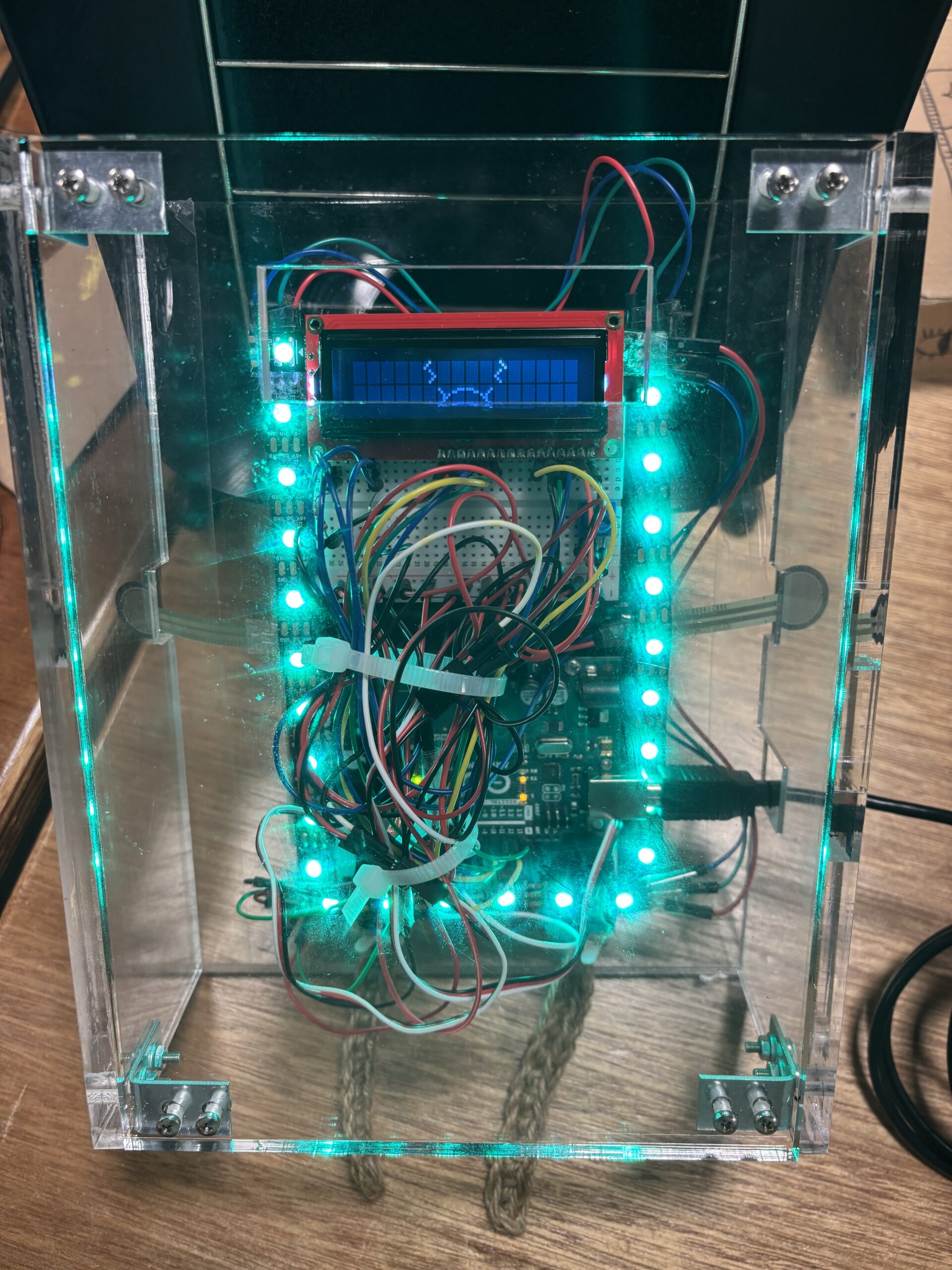

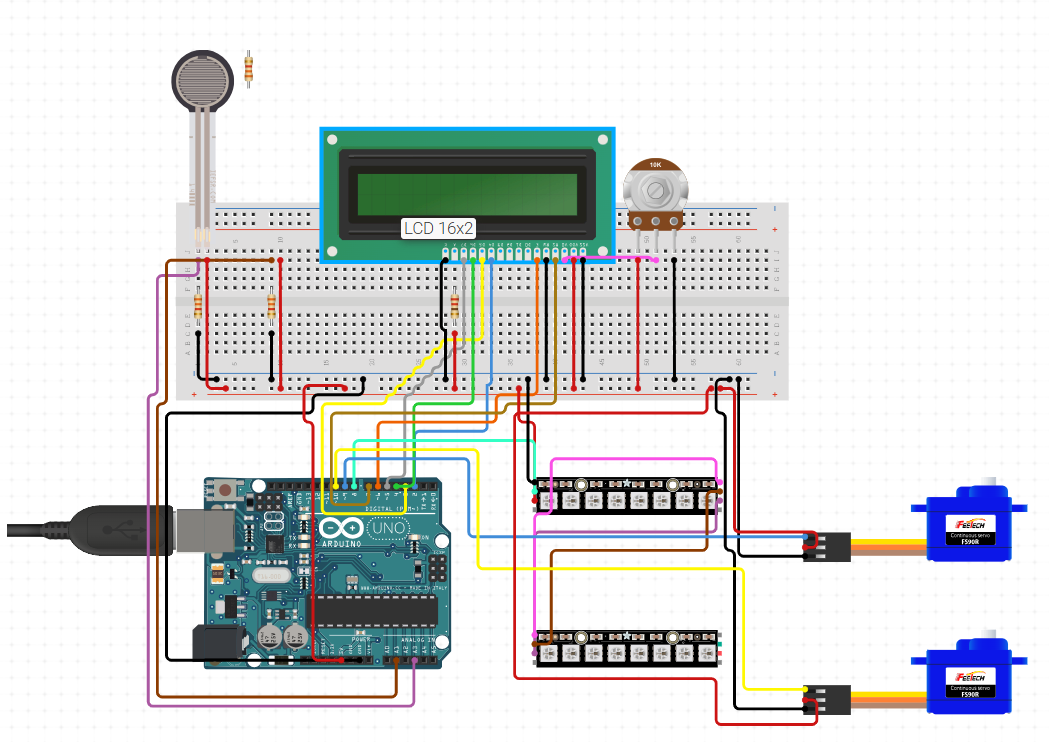

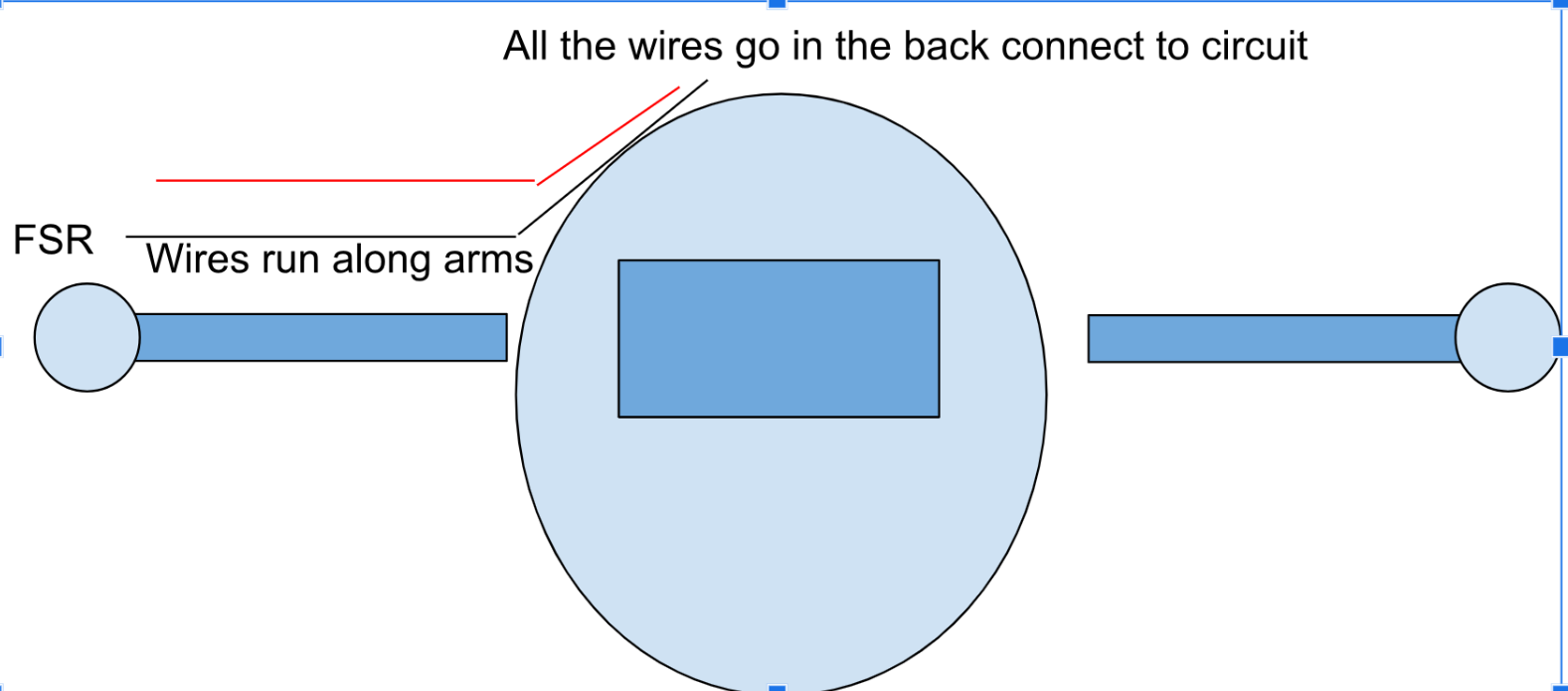

Here is the schematic of the circuit. One of the most challenging parts of this project was connecting all the wires and making sure they wouldn’t disconnect during transportation and during the showcase. I kept all the wires as far apart from each other as possible and made sure everything that could move them is nicely secured to the plate.

The making of the project

Making this project was a journey. What seemed to be a straight forward project turned out to be a 2 week long process of trial and error until I got the final result.

As I have mentioned above in the beginning the idea was to make the robot go through the maze on its own and have the user just set up the maze.

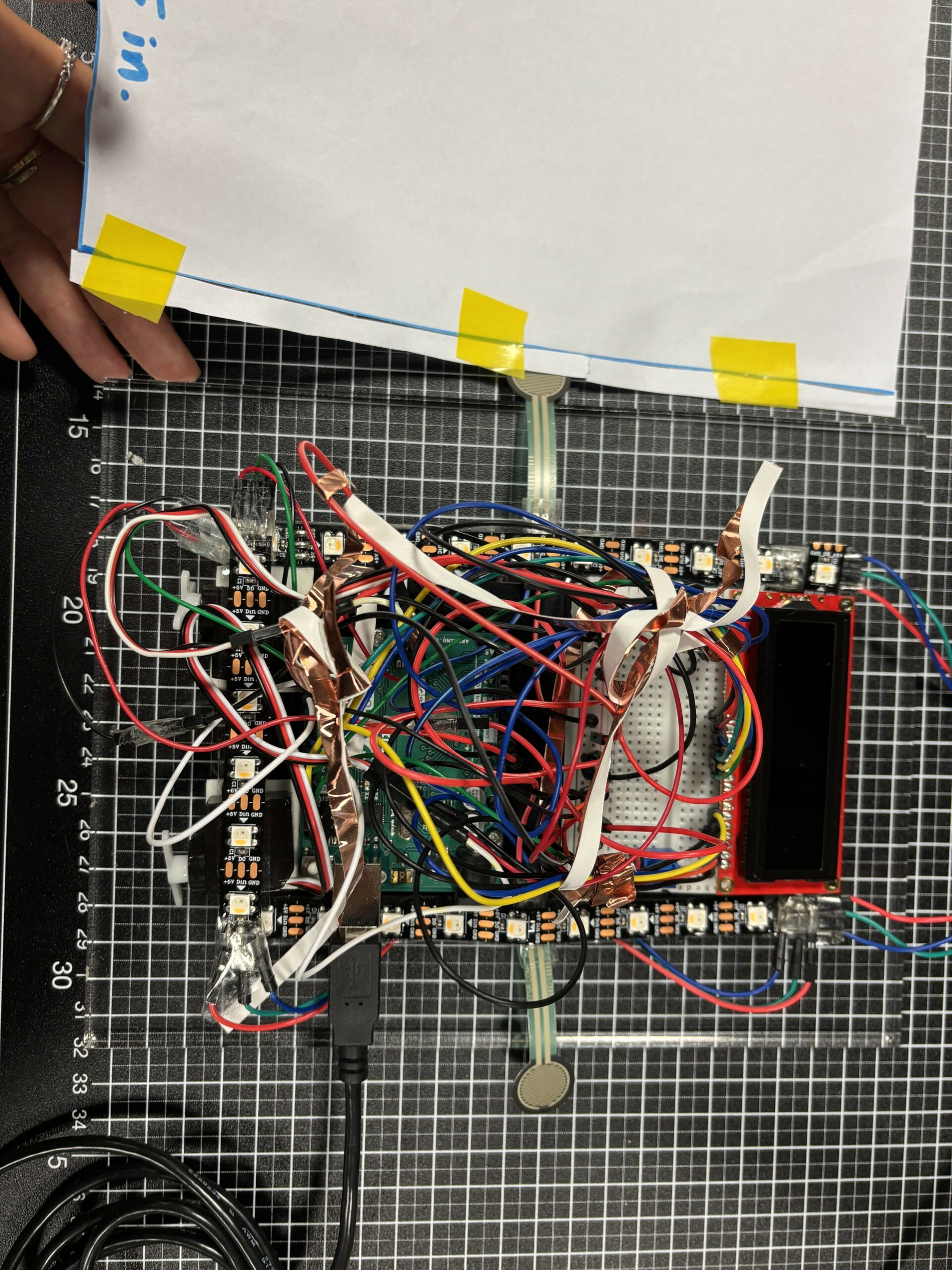

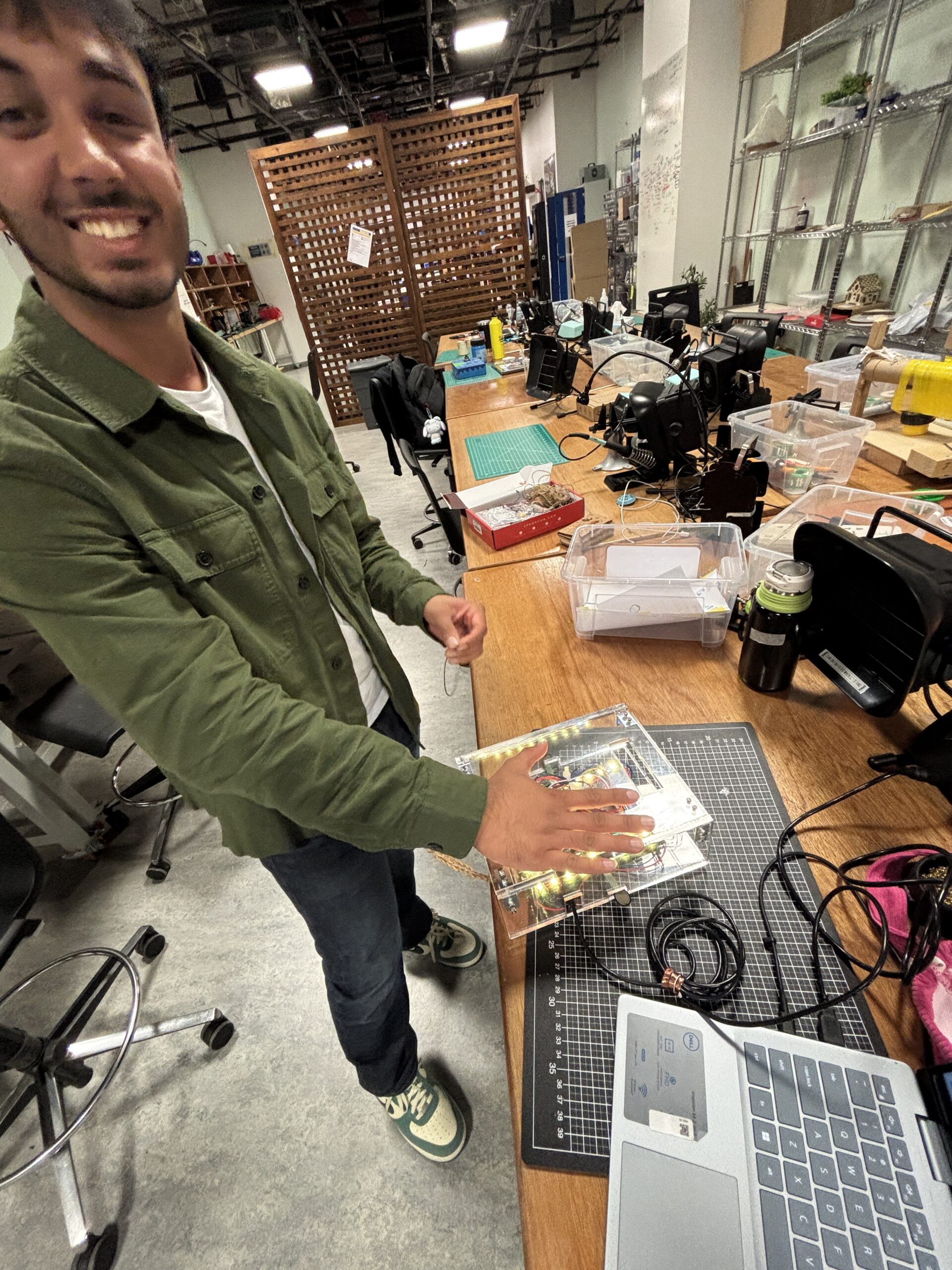

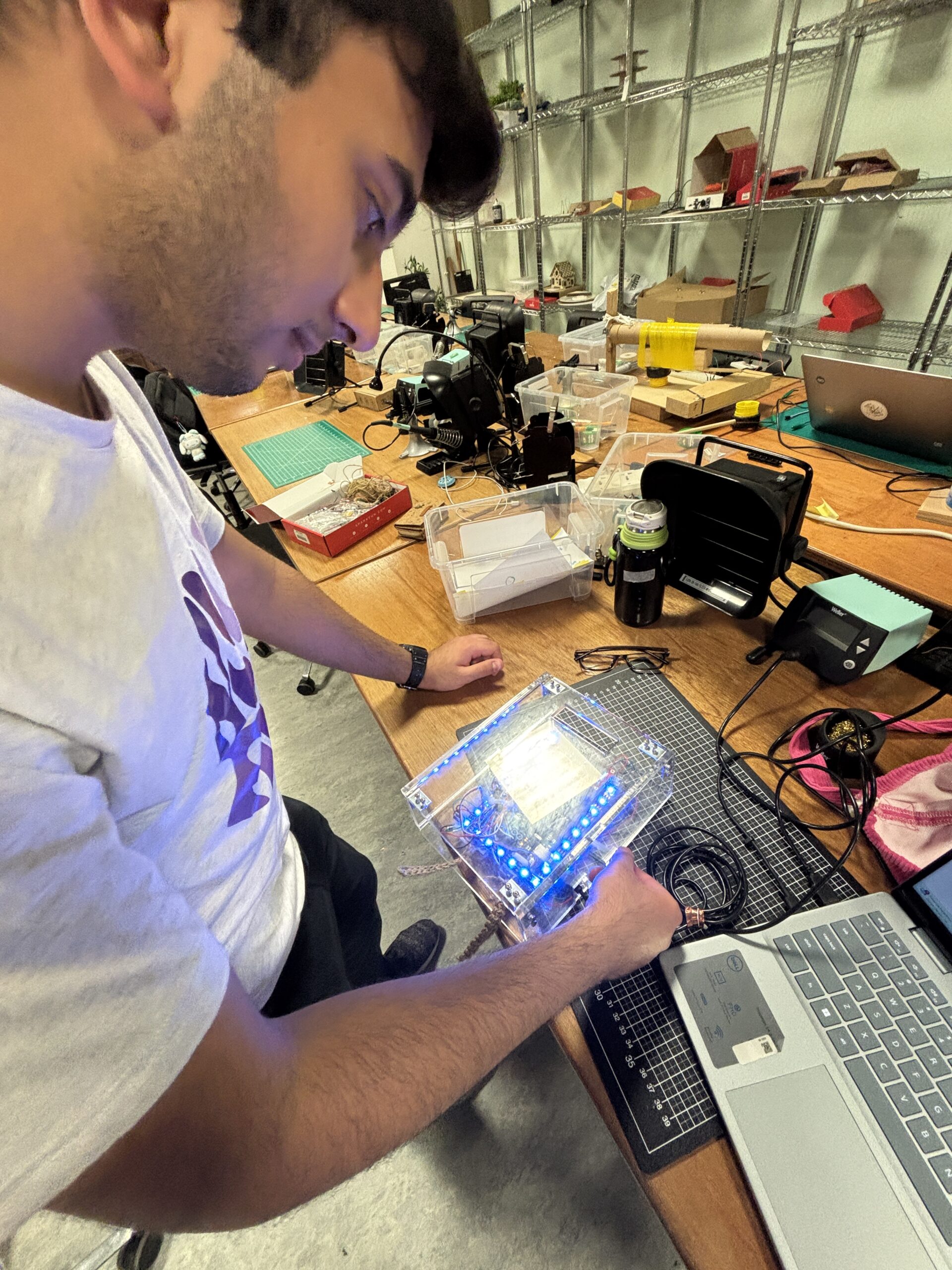

This is one of the photos of the early stages of development of the robot. As you can see it looks so much different than the final product. This was the part of the project where I was focusing on just getting the movement and some reading from the sensors.

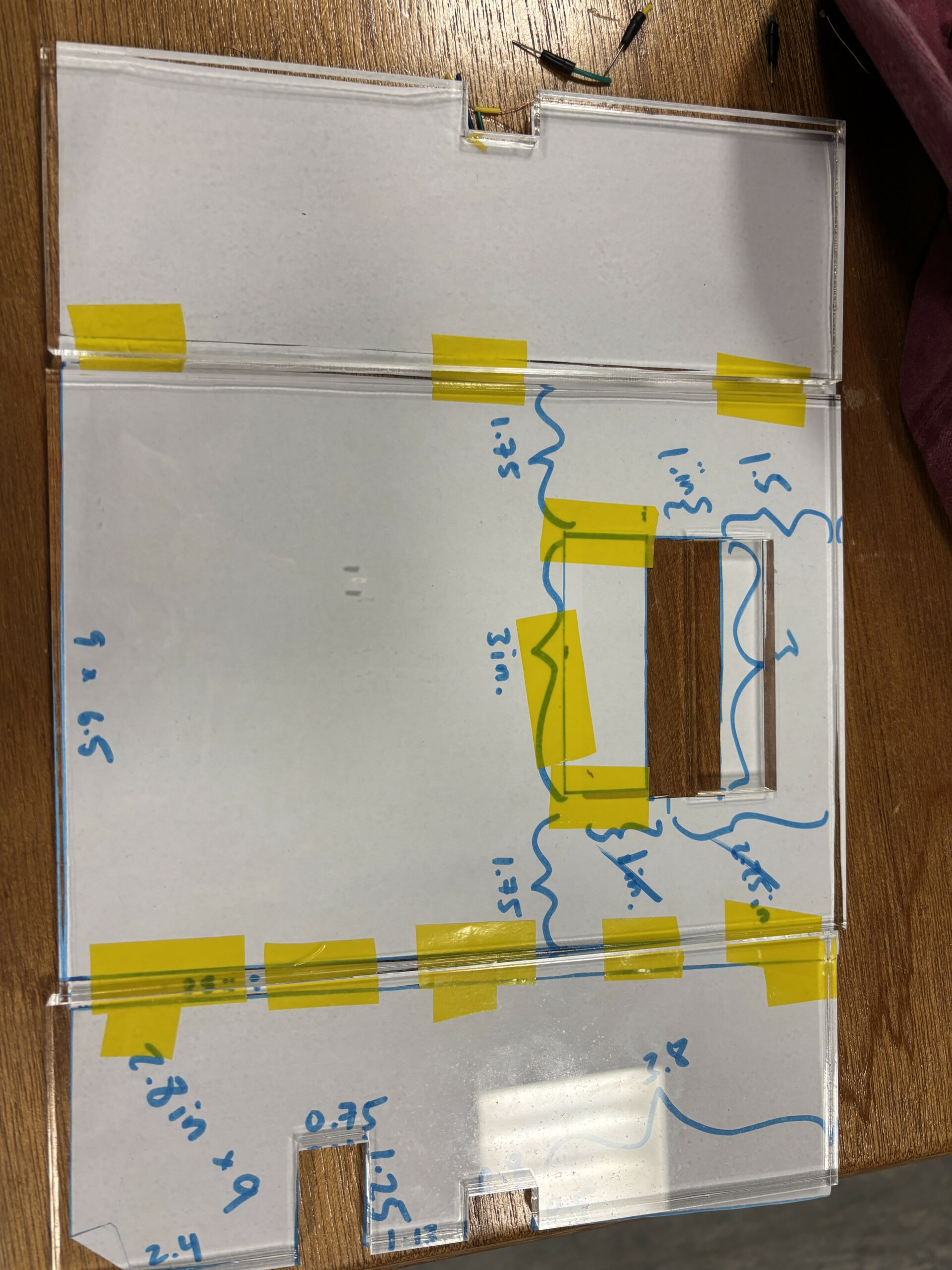

After I managed to get the movement done with the cable attached and with sending commands through my laptop I was ready to move on to the next phase which was adding 2 more sensors and having the robot move on its own. But before I could even do that I wanted to start working on the maze. The base of them maze was 120cm wide and 180cm tall, so if I put it up it would be roughly the same size as me. I also had to make the walls of the maze which were 20cm each in order to get picked up by the sensors on the robot. I also created temporary walls that could be moved by the users to give more interactivity to the project. This turned out to be much more of a time consuming and painful process than I thought because I had to use scraps of cardboard and make sure each peace is not only 20cm tall, but also that the cut on the side of the piece is straight enough so it can stick to the other piece. After that was done, testing for the autonomous movement was ready to start.

The movement seems to be alright, but if you watched carefully in the beginning the paperclip that was used as the 3rd wheel got a bit stuck on the cardboard. At the time of the recording of this video I didn’t think that would be an issue, but damn was I wrong. After more testing something scary started happening. The paperclip wouldn’t only get stuck a bit and make the robot slow down, it would actually fly right off the robot every time it got stuck. Also other problems came up, such as the robot constantly resetting in place every time it would start without a cable attached to it and also the third sensor not reading anything. So lets go through one problem at a time.

The problem with the robot resetting was very easy to debug and fix. The main reason something like that would be happening only when the cable is not plugged would mean something with the power is not alright. At the time I was using 4 1.5V batteries to power the motors of the robot as well as the Arduino which proved to be insufficient. The fix was to connect a 9V battery to the motors to allow the 1.5V batteries to be used just by the Arduino which fixed the problem. The next problem was the reading of the ultrasonic sensors. from all the wiring I have ran out of digital pins and had only one digital and one analog pin left for the sensor. After searching the internet I read that it should be fine since the analog pins can behave as digital, but my readings were still just 0. After talking with the professor who went through the source code of the Arduino he discovered that “Indeed there is a conversion table for pin numbers to their internal representations (bits in a port) and the table only includes the digital pins!”. The fix that the professor suggested and which ended up working is plugging the Echo pin in the analog one and the Trig in the digital. This helped me move on with the project and I would like to thank professor Shiloh one more time for saving me countless hours debugging!

Back to the movement issue. Because the paperclip kept getting stuck and flying off I had decided to remove it completely and instead use a wheel in the back which would act as support and allow the robot to move through all the bumps in the floor without a problem, or so I thought. After cutting the acrylic and getting the wheel in place I spent 2 hours trying to get the acrylic to stick to the base of the robot and in the process I superglued my finger to my phone which was not a fun experience at all! When I managed that I started the robot up and all seemed fine until I decided to try it out on the maze. Not only was the robot not detecting the walls, it was also not turning at all. After another countless hours of debugging here is what happened.

First of all the ultrasonic sensors are very unreliable which I found was the reason the robot wasn’t seeing the walls. Sometimes the reading would be 25 inches and would suddenly jump to 250inches which was impossible because it would mean the walls were too far apart. This was the main reason I decided to switch from an autonomous robot to the one that is controlled by the user. As for the movement, since the wheel was made out of rubber it created friction with the cardboard an it didn’t allow the robot to make a turn. It took me a lot of trial and error to realize the problem and come up with somewhat of the solution. I taped the the bottom up with clear duct tape which was slipping on the cardboard and allowed turning. The problem with this was the mentioned slipping, as one press of the button would make the robot go 360. I put in tape on the bottom of the cardboard which would stop that, but would also sometimes stop the turning mid way. In retrospect I would have saved myself so much trouble if I just let go of the idea of the cardboard floor!

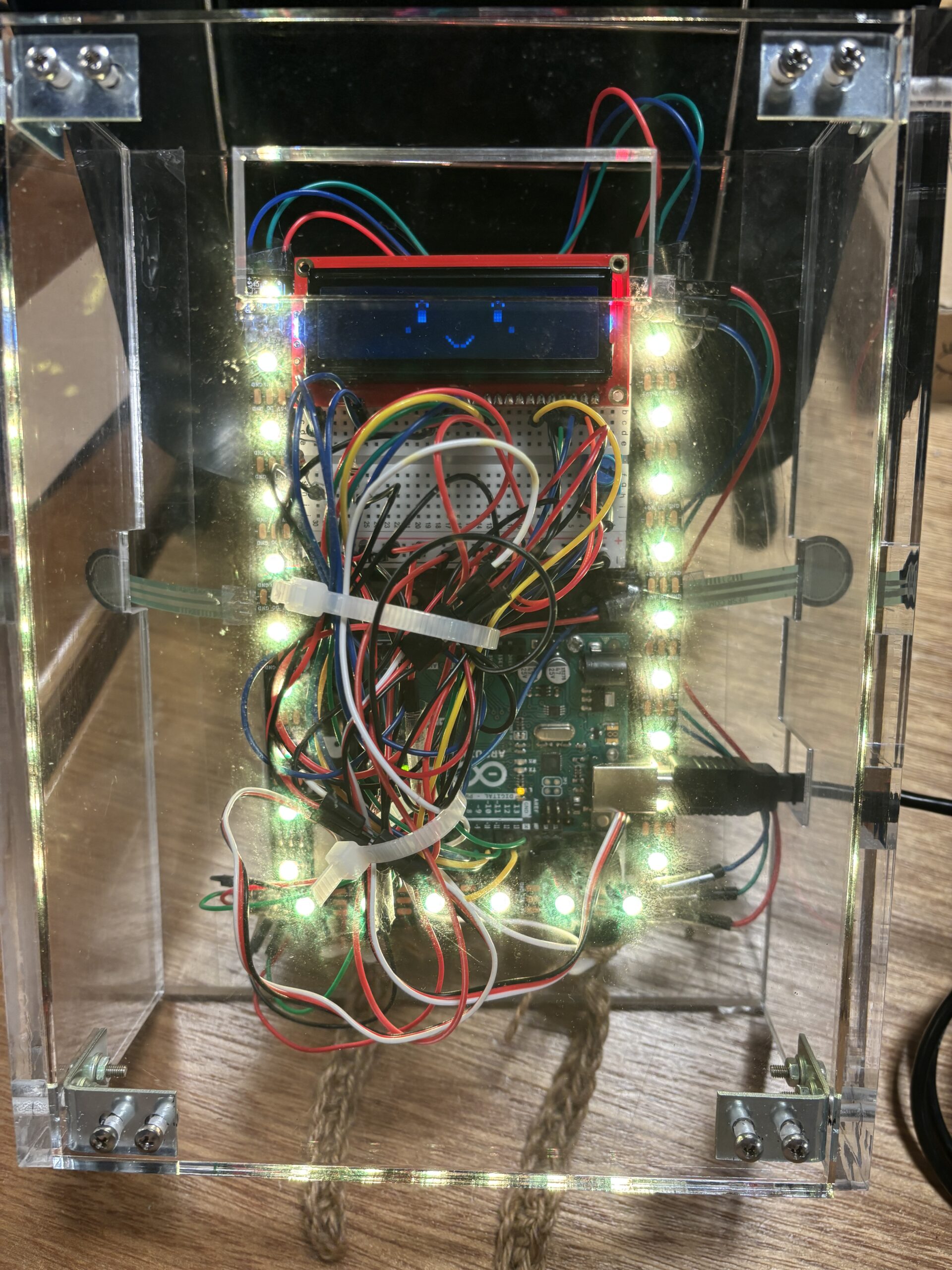

And so we come to the final design of the robot and the maze.

Areas of improvement

There are definitely some areas that could be worked on more in order to make the robot more functional. The first and most obvious one would be changing the cardboard floor with something else, perhaps something which doesn’t have bumps in it and wouldn’t create too much friction. Another thing is removing the back wheel and adding something else in its place, something that allows it to spin in place, but creates enough friction so the robot is not just spinning around in circles. I would also add an instructions page on the p5 as I have realized some users were confused on what to do when they approached the computer. Also I would try to find an alternative to the ultrasonic sensors and use something much more reliable which would allow the autonomous movement of the robot.

Things I am proud of and conclusion

I am honestly proud of the whole project. I think it is a great reflection of the things we have learned during the semester of Intro to IM and a great representation of how far we have come. When I started the course I didn’t even know how to connect wires to bake an LED light up, and here I am 14 weeks later making a robot that drives around the maze. Even though the journey to the end product was a bumpy one, I am grateful for everything I have learned in the process, every wire I had to cut and put back 20 times, all the sensors I went through to find the ones that work, all of it taught me valuable lessons and I am excited to start with new projects in the future. Thank you for reading through my journey through this class and I hope I will have a chance to write a blog again when I start my next project!