I enjoyed Tigoe’s piece about creating one’s work and then giving it the freedom to be experienced by the public. In the world of interactive art, instead of laying out your art with a manual, it’s about setting the stage and letting the audience be the audience. The main goal here is to direct a play, where the users aren’t told what to think or feel, but are provided with cues and props to navigate their journey. I would 100% prefer having the chance to figure out a task myself than to read a manual or to hear an explanation. It’s like teaching a friend a new card game and saying, “You’ll catch on as we play”. Of course, there will be a trial and error or some confusion but once you’re there, there’s an “ohhh” moment which is my favourite to experience and witness. This reading made me redefine interactivity in my head, it’s almost like figuring out someone’s piece is so stimulating it could in itself be the peak of the experience.

In the second reading, I liked the gloves work. Just as the author voices the importance of listening to the audience’s reactions and responses to the artwork, the discussion about sensor integration in gloves underscores the importance of understanding and responding to the gestures and movements of the user. This parallels the dynamic exchange described in the first reading, where meaning unfolds through the engagement between creator and audience.

Overall, both readings focus on the importance of creating interactive experiences that allow users to engage and contribute to the ongoing painting not a final product, whether through exploring an interactive artwork or experimenting with musical expression using gloves.

Month: April 2024

W11- Reading Reflection

Reading Bret Victor’s rant about the future of interaction design was eye opening to say the least. We often think that the top innovative ideas are those that revolve around advanced touch screens and improving computer interfaces such as the newly released Apple Vision Pro, which combines new technologies that utilizes 3D camera technology to act as a “spatial computer.” These are what people consider innovative and the future of interaction design. However, what if we go back to the basics in regards to interaction? What if we deeply think about how we interact with things? What allows us to interact with things? Victor proposes that the central component of the future of interaction design is hands. Hands? Yes, you heard it right! When I initially heard his proposition, I was perplexed. How could our hands be the future of innovation and interaction design?

As I reflected on Victor’s insights, I realized that the central component of innovation and interaction does not lie in the fancy touch screens we so happen to develop. In fact, the central components for such things are found on our bodies. In most cases, it is always our hands that allow for the concept of interaction to take place. Without them, I would go as far as to say the idea of interaction as we know of today might not exist. From the responses article, many were skeptical about the topic and say that hands cannot be the ultimate future for interaction design, that it would make us move a step backwards in the industry. Well, Victor and I choose to disagree.

If we go back in time and look at different forms of interaction design, nearly all projects require some form of interaction using the human hand, whether that is tying a shoe lace or even just moving objects in a virtual world. Even today, the most prominent forms of interaction design usually enforce human interaction using none other than our hands. Therefore, how can we claim that the human hand is not the future of interaction design when nearly all innovative projects use it as the main source of interaction? We cannot! This is why I truly believe that instead of pushing our humanity away in design, we should recognize that it is our hands that are the beginning and future of interaction design. Cool-looking interfaces and spatial computers are undeniably innovative creations but they are not the answers to our interactive future; they are merely tools that reflect our innate human essence, showcasing the power our hands can play in interaction design.

Week 10 – Reading Reflection

“Physical Computing’s Greatest Hits (and Misses)” provides a comprehensive overview of some projects and their applications in the area of physical computing. The examples explore from musical instruments like the Theremin to more advanced concepts like robotics. Each project showcases innovative ways of interfacing with technology through physical gestures or interactions. However, it also makes me think that there are limitations for these successes. For instance, while projects like video mirrors or body-as-cursor offer good ways of interaction, they often lack meaningful engagement or structured feedback. Similarly, remote hugs aim to convey emotions over a network but struggle to replicate the warmth and intimacy of physical touch humans have. Hence, these examples highlight the challenge of bridging the gap between technological capability and human experience in physical computing.

The reading “Making Interactive Art: Set the Stage, Then Shut Up and Listen” presents an analysis against providing explicit interpretations in interactive art. It emphasizes the importance of allowing the audience to engage with the artwork independently, without being directed on how to interpret or interact with it. This notion resonates with several real-life experiences, such as the role of a director working with actors in a theater play. In both scenarios, providing too much guidance or interpretation can suppress creativity and limit the potential for meaningful engagement. Instead, the author suggests creating an environment that encourages exploration and interpretation. Just as actors bring their unique interpretation to a role, audiences bring their own perspectives and emotions to interactive artworks. Therefore, by stepping back and allowing for open interpretation and interaction, artists can facilitate richer and more personal connections between their work and their audience.

Pi : Week 11 Reading – The Feel Factor: Escaping the Flatland of Modern Interfaces

Whenever I do the Interactive Media reading assignments, I almost always disagree or criticize the author, or make fun of their claims. But this week will be different. Bret Victor is one of the only two people I idolized when I was a child and one day hope to be like. Whatever those two men (the childhood heroes) say, I will always agree with them 😉 .

I work in the field of haptics – the science of touch. My supervisor once explained that when a human uses a particular tool for long, he becomes too much accustomed to that tool. For example, think of the carpenters, painters, guitarists, etc.

This continues to the extent that the tool becomes a part of his body, and his means to sense the world.

But in order for that tool to become an extension of his body, the tool must give the user “good tangible feedback.” And that kind of feedback is something digital devices truly lack. Try using an actual ruler to measure the length of something… Now try measuring the same distance using the measurement app in the iPad, which is technically intricate, but very cumbersome to use. It just does not feel like a ruler.

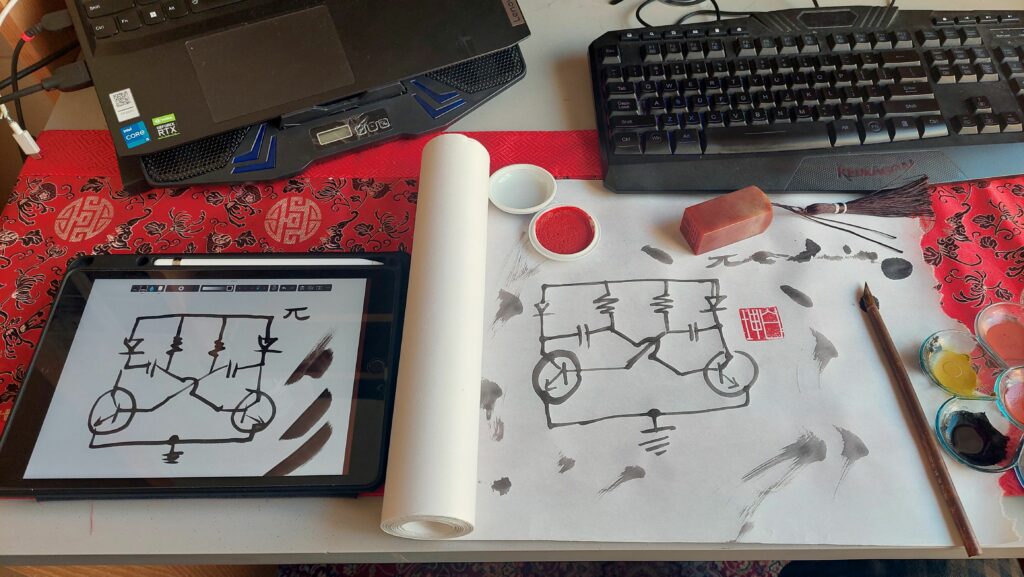

For one of my personal projects, I draw circuit diagrams with Chinese traditional ink on rice paper—to imagine an alternate universe, where electricity and the industrial revolution have started from the Orient.

In this project, I tried and evaluated two methods: the iPad method and the literal ink method. Somebody whose eyes are not trained will tell you that the results are nearly the same. Thu, in reality, both methods work. However, for my artistic satisfaction, the iPad approach was a disaster. Though I am using a state of the art Chinese brush simulator, I could not feel the resistance of the paper, the ink was flowing, the brush was scratching the paper, and so on, ad infinitum.

The approach towards the iPad was simply soulless. Thus, Bret’s vision—or better said, his criticism on the lack of vision in the current design trends—had a deep echo with my experiences. “Our hands feel things and our hands manipulate things. Why shoot for anything less than a dynamic medium that we can see, feel, and manipulate?” This should be written on the wall of each tech company urging to birth the next iteration of soulless gadgets into existence.

No manner of me waving a stylus around is going to recreate the sensory feedback of ink travelling down to paper through my ink brush.

In short, the iPad stylus will never become an extension to my body, like the real paintbrush does.

“Hands feel things, and hands manipulate things,” Bret points out ; I couldn’t but smile to see that most modern designs spectacularly reject this in a fashion way over the top.

I really love Bret’s equivalent of the whole “Pictures Under Glass” idea to how utterly ridiculous it would have been if someone had once said, “black-and-white is the future of photography.”

In conclusion, Bret’s rant isn’t just a criticism; it’s a roadmap for future innovators.

Bret did not give us a solution, but a question to ponder. This question alone should challenge us to look for something beyond the conventional in thinking about how we make our interactions with technology as instinctive as moving our limbs, as natural as using your hands.

Week 10 Response – Tom Igoe

Tom Igoe’s articles on physical computing and interactive art describe the growing relationship between technology and user engagement. In Physical Computing’s Greatest Hits (and Misses), Igoe talks about the relationship between creativity and technology, highlighting how simple designs can provoke complex interactions and reflections. Additionally, in Making Interactive Art: Set the Stage, Then Shut Up and Listen, he advocates for a minimalistic approach in guiding the audience’s experience by using the art of subtlety in interactive design.

Igoe’s philosophy resonates deeply with me; it challenges the beauty of discovery within the constraints of design and technology, reminding creators to trust their audience’s intuitive interactions with their work. .

Week 10 Reading Reflection

I enjoyed both readings. The number of discussions and reading materials covering user interactions in our course so far is quite intriguing to me. Different thoughts on user interactions has also been very interesting. Is user interaction supposed to be simple or authentic?

Reflecting on Tom Igoe’s insights into interactive design, I am increasingly captivated by the potential for sensor-driven art to create immersive environments. For instance, envisioning a virtual landscape that responds not just to the location but also the pressure of a hand is exhilarating. Light interactions could simulate natural phenomena such as rustling leaves, while stronger interactions might alter weather or time settings, offering a vivid, multisensory experience. This technology could revolutionize educational environments by enabling museum visitors to interact with exhibits in ways that make learning intuitive and engaging. Similarly, in physical therapy, such technologies could provide exciting ways to engage patients and monitor their progress by gamifying therapeutic activities.

Igoe’s emphasis on the principle of “shutting up and listening” deeply resonates with me, highlighting the importance of observing how users interact with a design to identify improvement areas. This principle has been pivotal in my projects, particularly in video game development, where soliciting real-time feedback has been crucial. These interactions provide direct insights into the user experience, invaluable for refining game mechanics.

Moreover, his discussions on physical computing, where technologies like Floor Pads and interactive elements such as Scooby-Doo Paintings illustrate the seamless integration of user interaction and technology, have been enlightening. These technologies enhance traditional experiences like art viewing with modern technological interactions, suggesting new ways to engage audiences.

Igoe’s focus on the iterative nature of design through “user-testing” has reshaped my approach to interactive projects. This ongoing dialogue with users is not just a step in the process but a continuous part of the creative cycle, essential for refining and evolving a project. This perspective encourages me to remain open to feedback and committed to innovation, reinforcing the transformative impact of user-centered design and technology in expanding the boundaries of traditional media and interactive environments.

Week 10 Analog input & output

For this week’s assignment, I have implemented a small lighting system that interfaces both analog and digital sensors.

The task was to use at least one analog sensor and one digital sensor to control two LEDs differently—one in a digital fashion and the other in an analog fashion. For this, I used:

- Analog sensor: A photoresistor to sense ambient light levels.

- Digital sensor: A tactile button switch to change modes.

- LEDs: A standard LED and an RGB LED for digital and analog control, respectively.

I have used the tactile button and the photoresistor to control the RGB LED in two distinct modes: Night Mode and Party Mode.

- Night Mode: The RGB LED’s behavior is influenced by the ambient light level detected by the photoresistor. When it’s dark, the RGB LED cycles through colors at a slower pace, providing a soothing nighttime light effect.

- Party Mode: Activated by pressing the tactile button, this mode turns on an additional LED indicator to show that Party Mode is active. In this mode, the RGB LED cycles through colors more quickly, creating a dynamic and festive atmosphere.

The tactile button toggles between these two modes, allowing the RGB LED to adapt its behavior based on the selected mode and the ambient light conditions.

The button debouncing was tricky for me. Button debouncing is basically managing the button input to toggle between normal and party modes without accidental triggers.

int reading = digitalRead(A1);

if (reading != lastButtonState) {

lastDebounceTime = millis(); // Reset the debouncing timer

}

if ((millis() - lastDebounceTime) > debounceDelay) {

if (reading != buttonState) {

buttonState = reading;

if (buttonState == HIGH) {

partyMode = !partyMode;

digitalWrite(8, partyMode ? HIGH : LOW);

}

}

}

lastButtonState = reading;

Another challenging part was figuring out the color change minimally. I used bitwise operations for this.

if (!partyMode && sensorValue >= 400) {

digitalWrite(10, LOW);

digitalWrite(11, LOW);

digitalWrite(12, LOW);

} else {

int interval = partyMode ? partyInterval : normalInterval;

if (millis() - lastChangeTime >= interval) {

lastChangeTime = millis();

rgbLedState = (rgbLedState + 1) % 8;

// Determine which LEDs to turn on based on the current state

digitalWrite(10, (rgbLedState & 0x01) ? HIGH : LOW); // Red

digitalWrite(11, (rgbLedState & 0x02) ? HIGH : LOW); // Green

digitalWrite(12, (rgbLedState & 0x04) ? HIGH : LOW); // Blue

}

}

Week 9-Analog Input & Output

Concept

As part of the 9th Assignment of Intro to IM, we were tasked with the objective of reading input from at least one analog sensor, and at least one digital sensor (switch). This data would then be used to control at least two LEDs, one in a digital fashion and the other in an analog fashion, in some creative way.

The core idea of my project is to create an interactive light experience using a combination of analog and digital inputs to control an RGB LED in a creative and visually appealing manner. Initially, the RGB LED displays a steady red color, which gradually transitions through a spectrum of colors, creating a calming and dynamic visual effect. This smooth color transition continues indefinitely, creating a mesmerizing ambient display.

The interaction becomes more engaging with the introduction of a user-controlled digital button and a light sensor. The button, when pressed, shifts the mode of the LED from its continuous color transition to a responsive blinking state. In this state, the color of the LED’s blinking is determined by the ambient light level measured by the sensor. Specifically:

- Below 300 units: The LED blinks in red, indicating low light conditions.

- Between 300 and 900 units: The LED blinks in blue, corresponding to moderate light levels.

- Above 900 units: The LED blinks in green, signifying high light intensity.

Implementation

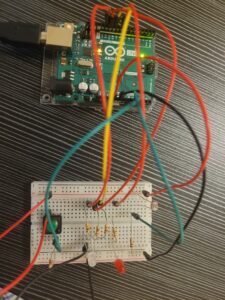

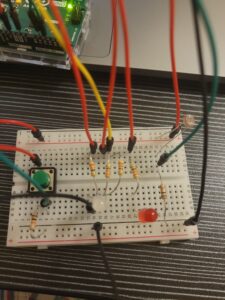

Pictures of Circuit

With this, I produced the following circuit:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Demo Video

A demo video, in detail, can be seen here:

Difficulties & Improvements

While the concept of the color transition was straightforward, implementing it in Arduino presented significant challenges. Determining the correct method for transitioning from one color to another smoothly, without abrupt changes, was particularly tricky. This aspect of the project required careful tweaking of the code to ensure that the color shifts were visually pleasing.

void smoothColorTransition() {

// Fade colors smoothly

if (redValue > 0 && blueValue == 0) {

redValue -= step;

greenValue += step;

}

if (greenValue > 0 && redValue == 0) {

greenValue -= step;

blueValue += step;

}

if (blueValue > 0 && greenValue == 0) {

blueValue -= step;

redValue += step;

}

Despite these challenges, I thoroughly enjoyed this part of the project. It was rewarding to see the seamless color transitions come to life. Looking ahead, I plan to expand this project by adding an additional LED and another button to enhance interactivity and complexity, making the experience even more engaging.

Week 10 Assignment – “Who’s First?”

For this assignment, I had a hard time coming up with a creative idea. My twin nephews were over at the time, and I could hear them arguing about something. When I checked up on them, they were fighting over whoever was faster than the other, so I decided to make something to settle that (Love you, Ahmed and Jassim).

The concept is pretty simple:

It’s a two-player game. One player gets the photoreceptor, and the other gets the button. Whoever can cause their light to flash first proves that they’re faster than the other.

Materials Used:

- 2x 330 resistors

- 2x 10k resistors

- 8x wires

- 2x LEDs (one Red, one Yellow)

- 1x button

- 1x photoresistor

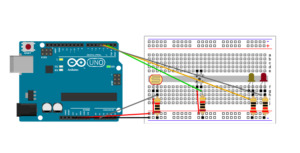

Setup:

I used examples from previous classes to piggyback on. The slides were very helpful to me.

The website I used will NOT be used again. Although I faced many problems with the resistors, it got the job done.

Code:

int photoSensorPin = A1;

int buttonPin = 2;

int ledPin1 = 3;

int ledPin2 = 4;

void setup() {

pinMode(photoSensorPin, INPUT);

pinMode(buttonPin, INPUT);

pinMode(ledPin1, OUTPUT);

pinMode(ledPin2, OUTPUT);

}

void loop() {

int sensorValue = analogRead(photoSensorPin);

int buttonState = digitalRead(buttonPin);

if (buttonState == HIGH) {

digitalWrite(ledPin1, LOW);

digitalWrite(ledPin2, HIGH);

} else if (sensorValue < 450) {

digitalWrite(ledPin1, HIGH);

digitalWrite(ledPin2, LOW);

} else {

digitalWrite(ledPin1, LOW);

digitalWrite(ledPin2, LOW);

}

}

Demo:

Reflection:

Making this game was a pretty fun challenge for me. This language is very new to me, and I’m still having issues getting used to it. I would like to take this a step further and possibly use other forms of input devices to accurately guess who’s faster (Ahmed won BTW).

Week 10 Reading Reflection

Reflection on “Physical Computing’s Greatest Hits (and misses)”

In “Physical Computing’s Greatest Hits (and misses),” the complex interplay between user interaction and physical computing physics is masterfully broken down. The article examines the ways in which different initiatives seek to build a connection between digital response and human engagement. The investigation of technologies that aid in meditation strikes me as particularly noteworthy. Being a tech and mindfulness fan, I find it fascinating and a little frightening that an essentially qualitative experience can be quantified. Are these devices making the spiritual journey better, or are they just turning it into a set of numbers? This query calls for a more thorough examination of technology’s place in settings that are often designated for pure human experience.

“Digital Wheel Art,” another noteworthy initiative that was highlighted, demonstrates how technology may democratize the creation of art, particularly for people with restricted mobility. It serves as a sobering reminder that technological accessibility is a bridge to equality and self-expression rather than merely a feature. This, together with the creative Sign Language gloves, strengthens my conviction that technology, when used carefully, can serve as a potent force for inclusion rather than just serving a practical purpose.

These illustrations highlight a more general insight that was brought to light by the reading: interactive installations are more than just impressive technical feats; they also reveal human stories and arouse feelings. Therefore, interactive art’s value lies not only in its technological prowess but also in its capacity to speak to our common humanity and elicit a wide range of emotions.

Reflection on “Making Interactive Art: Set the Stage, Then Shut Up and Listen”

With regard to the function of the artist in the age of interactive media, “Making Interactive Art: Set the Stage, Then Shut Up and Listen” presents an interesting perspective. According to the reading, interactive art ought to be a conversation rather than a monologue—a platform for engagement rather than only observation. This speaks to me, especially when it comes to the fear that an artist may have that their creations would be misinterpreted or inappropriately used. The act of giving up control and letting the audience add their own interpretations to the work is evidence of the transformational potential of art.

The spectrum of engagement that creators struggle with is highlighted by the tension between interaction and set narrative, such as that seen in video games or visual novels. These media contest the idea that interactive equals natural, unscripted experiences, proposing instead that the audience’s interpretation and the artist’s intention are complementary elements of a nuanced dialogue.

Thinking about this makes me wonder about the fine line that all artists have to walk. In order to create an environment where art and audience can collaboratively generate meaning, curation involves more than just designing the experience. It also involves managing the lack of direction. It’s a subtle, yet audacious, gesture of faith in the audience’s ability to connect with the work of art, giving each encounter a distinct personality. My comprehension of interactive art has grown as a result of this study, and I now have a greater respect for the bravery and vulnerability that these works of art require.