The author’s humble introduction, where he admitted that none of us truly have a crystal-clear understanding of what interactivity is, immediately resonated with me. It’s a sentiment many of us can relate to – we often have a sense of what certain concepts mean, but articulating a precise definition can be difficult to find.

The idea of using the conversation between Fredegund and Gomer as an example to define interactivity was a pleasant surprise. It underscored the importance of key elements in any interactive exchange: listening, thinking, and speaking. It made me realize that without these components, a conversation can hardly be considered truly interactive; instead, it becomes a one-way process, lacking the depth and richness of true interaction.

The analogy of actors and a branch of a tree further clarified the concept. I’ve always believed that interactions are a two-way street, and when I engage with someone new, I often observe how they perceive the interactive process. Do they view it as a collaborative effort, like the intertwining branches of a tree, or is it merely a one-sided performance?

Prior to reading the article, I was uncertain about what qualified as interactive and what did not. The depiction of interactivity into different levels provided me with a valuable framework for understanding and categorizing interactive experiences.

However, it was the author’s explanation about the importance of listening that truly resonated with me. Each sentence in that section felt relatable. We’ve all encountered individuals who do not truly listen, and the negative vibe they emanate in such interactions is noticeable. Conversely, engaging with someone who not only listens but comprehends and engages with our thoughts is an immensely positive experience.

In conclusion, the article shed light on the multifaceted nature of interactivity and the crucial role of listening, thinking, and speaking in fostering meaningful interactions. It provided clarity on what constitutes true interactivity and offered a humorous take on subjective perspectives. Ultimately, it reminded me that genuine interactions are a delicate balance of engagement, empathy, and active participation.

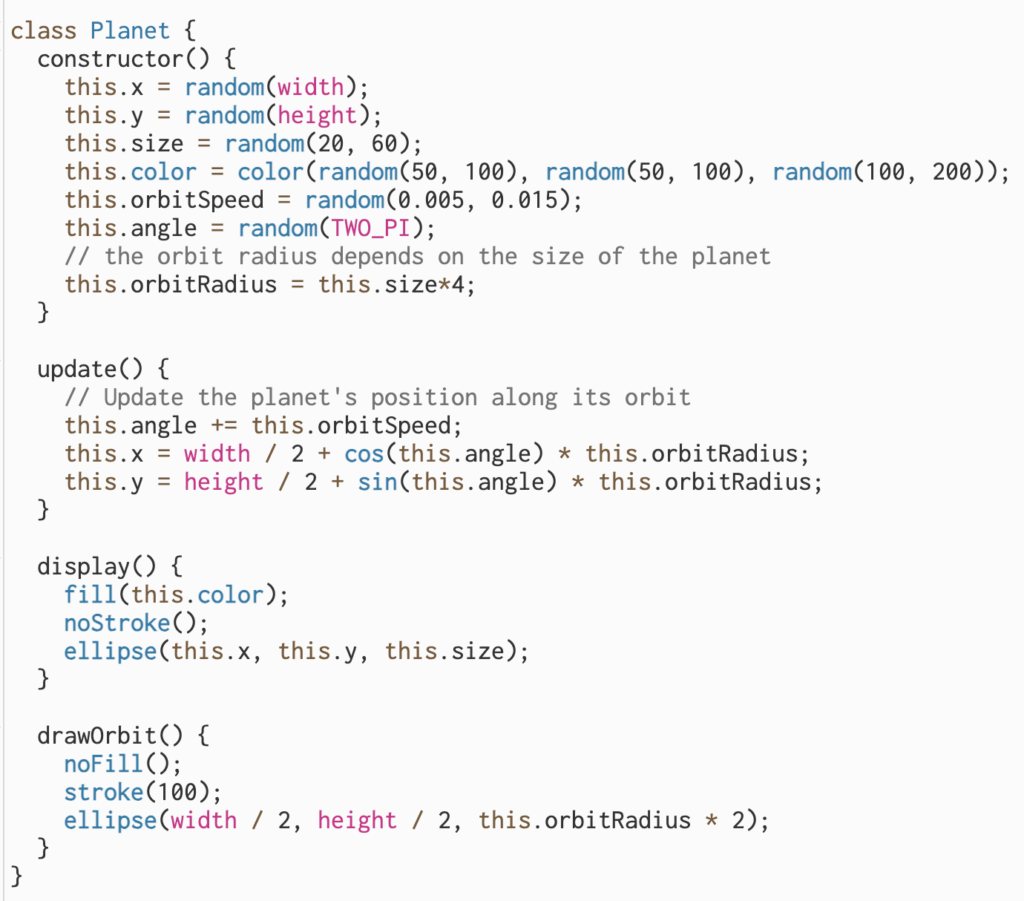

Sketch:

Sketch: