Whenever I do the Interactive Media reading assignments, I almost always disagree or criticize the author, or make fun of their claims. But this week will be different. Bret Victor is one of the only two people I idolized when I was a child and one day hope to be like. Whatever those two men (the childhood heroes) say, I will always agree with them 😉 .

I work in the field of haptics – the science of touch. My supervisor once explained that when a human uses a particular tool for long, he becomes too much accustomed to that tool. For example, think of the carpenters, painters, guitarists, etc.

This continues to the extent that the tool becomes a part of his body, and his means to sense the world.

But in order for that tool to become an extension of his body, the tool must give the user “good tangible feedback.” And that kind of feedback is something digital devices truly lack. Try using an actual ruler to measure the length of something… Now try measuring the same distance using the measurement app in the iPad, which is technically intricate, but very cumbersome to use. It just does not feel like a ruler.

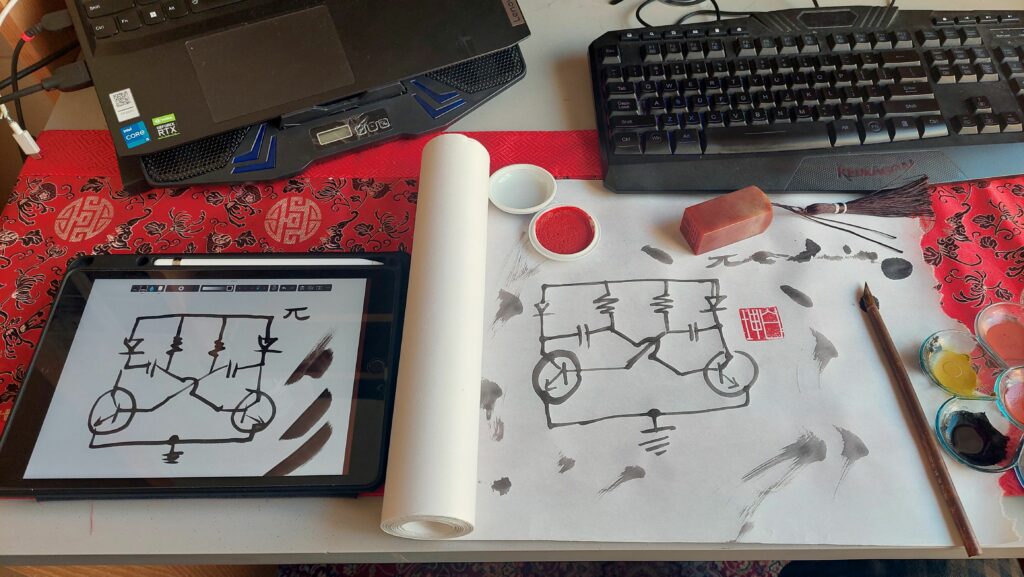

For one of my personal projects, I draw circuit diagrams with Chinese traditional ink on rice paper—to imagine an alternate universe, where electricity and the industrial revolution have started from the Orient.

In this project, I tried and evaluated two methods: the iPad method and the literal ink method. Somebody whose eyes are not trained will tell you that the results are nearly the same. Thu, in reality, both methods work. However, for my artistic satisfaction, the iPad approach was a disaster. Though I am using a state of the art Chinese brush simulator, I could not feel the resistance of the paper, the ink was flowing, the brush was scratching the paper, and so on, ad infinitum.

The approach towards the iPad was simply soulless. Thus, Bret’s vision—or better said, his criticism on the lack of vision in the current design trends—had a deep echo with my experiences. “Our hands feel things and our hands manipulate things. Why shoot for anything less than a dynamic medium that we can see, feel, and manipulate?” This should be written on the wall of each tech company urging to birth the next iteration of soulless gadgets into existence.

No manner of me waving a stylus around is going to recreate the sensory feedback of ink travelling down to paper through my ink brush.

In short, the iPad stylus will never become an extension to my body, like the real paintbrush does.

“Hands feel things, and hands manipulate things,” Bret points out ; I couldn’t but smile to see that most modern designs spectacularly reject this in a fashion way over the top.

I really love Bret’s equivalent of the whole “Pictures Under Glass” idea to how utterly ridiculous it would have been if someone had once said, “black-and-white is the future of photography.”

In conclusion, Bret’s rant isn’t just a criticism; it’s a roadmap for future innovators.

Bret did not give us a solution, but a question to ponder. This question alone should challenge us to look for something beyond the conventional in thinking about how we make our interactions with technology as instinctive as moving our limbs, as natural as using your hands.