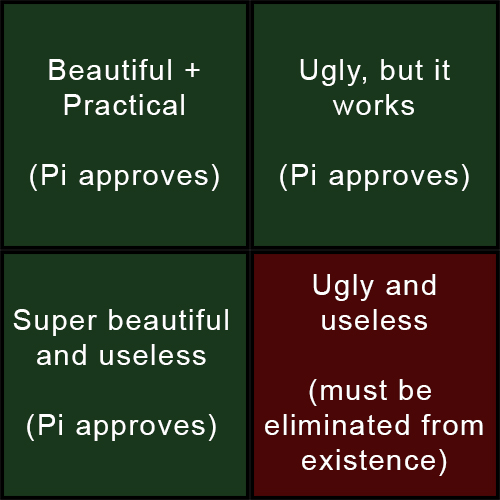

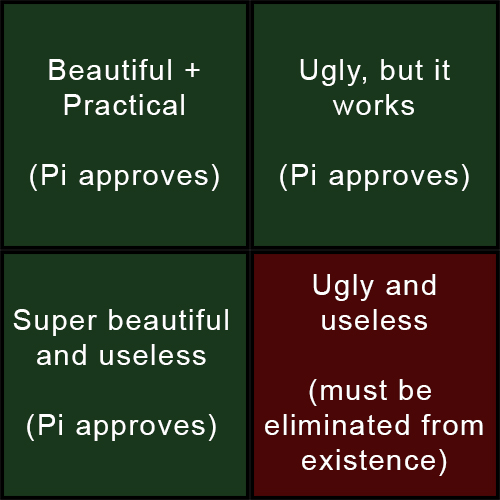

Written on my dorm wall, there is a manifesto that reads “Aesthetical Practicality Manifesto…There is no right or wrong, only what is practical and what is not…Anything which is not of utmost practicality, intense beauty, or ideally, a blend of both, is bullshit, and must be always avoided.”

Reading through Norman’s “Emotion & Design: Attractive things work better,” to me, was like I heard a harmonic echo of my thoughts. Juxtaposition by Norman to show the weaving of practicality and aesthetics in design, is what I so strongly support. In short, my life is super simple. I just follow the following with almost everything in my life.

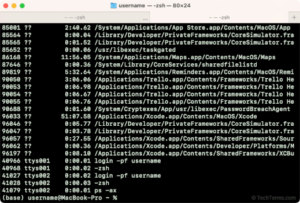

First up, Norman’s opening on affect and design captures a simple truth: “Advances in our understanding of emotion and affect have implications for the science of design.” This one has always resonated with me. In my quest to blend the roles of a engineer with an artist, I understood that emotion is not a byproduct but the guiding force in the process. Norman words that nicely, “Positive affect can make complex tasks feel easier; negative affect does the opposite. His story of the color displays in computers, which was once thought to be superfluous but later turning out to be very necessary and practical, though not making any practical benefit at all, was absolutely representative of this principle. I still think about his words whenever I try to beautify my computer terminals with themes and eveything, while in reality, there is nothing of practical value… but having a Batman/Ironman like computer User Interface improves my motivation to work by hundredfold.

Norman’s teapot examples are a treasure trove of insights. The pot by Carelman, unus unusable teapot by Nanna, and a tilting pot by Ronnefeldt represent, in a nutshell, the whole spectrum of design philosophies: from functionally unpractical, through aesthetically awkward and unwieldy but serving its purpose, all the way to functional sophistication. Just the way Norman believes, I think form is function.

I do not see aesthetics and usability in opposition but as dance partners. One reinforces the other’s strength. When Norman poses, “Why not beauty and brains, pleasure and usability?” I find myself nodding in agreement. This mirrors the core tenet of my manifestoᅳthat of the achievement of practicality so palpable but in the most beautiful aesthetic way possible. Such is very key in my work at the intersection between technology and art. For example, take the development in software engineering for user interfaces. A visually appealing interface that confounds the user is as ineffective as a drab but functional one.

We really need interfaces that are pleasant to the eyes, at the same time taking the user around effectivelyᅳbasically, nice skeuomorphic designs that I have always admired.

Another very deep reflection I like is Norman’s argument about affect in design. He shows how our emotions and fears make us change our minds altogether about the difficulty of the task, using the example of the plank at different heights. In the professional world, I have seen firsthand that the right emotional design can make the use of even a complex piece of software feel approachableᅳor perhaps even actually fun. Norman’s statement, “Positive affect can make it easier to do difficult tasks,” exactly supports my belief in the attractive design improving the interaction with the product and hence letting the difficulty of the task be gone. But if anything, that’s a critique I might level against Norman: It would be how he treats the friction of usability against aesthetics. While he does fully grasp said friction, I think there’s leeway for a much more intricate exploration of how the two can be married together more cohesively in the design process.

My manifesto demands that once tangible practicality is demonstrated, achieving aesthetics is paramount.

This is where the art of design truly lies – in not just balancing but synthesizing function and form. Norman reflecting on the importance of good human-centered design in stressful situations is something I absolutely agree with. He underscores the importance of empathetic designs that take into account the emotional state of the user. This principle can be transferred from physical products to digital interfaces, where ease and clarity in navigation can do a lot not to stress users. In summary, the discourse of Norman reinstated to me what I had believed all along: aesthetic and practicality is basically a conglomeration.

GUI

GUI Terminal Interface

Terminal Interface